Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 1, P. 34

Research shows overweight and obesity are associated with several different types of cancers.

Excess body weight may be as dangerous as smoking when it comes to cancer, but few Americans are aware of this important modifiable risk factor.

According to two recently published reviews, excess body fatness raises the risk of at least 13 kinds of cancer.1,2 This isn’t news to cancer researchers, but it’s news to Americans, about one-half of whom are unaware of any link between cancer and weight.3 “As far as lifestyle factors, next to not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight is the most important thing people can do to keep their cancer risk lower,” says Alice G. Bender, MS, RDN, head of nutrition programs at the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR). “But a lot of Americans feel there’s nothing they can do about cancer. They don’t see a lifestyle link.”

Data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ 2015 Health, United States report, show that 70.7% of adults aged 20 and older are overweight, with 37.9% falling into the obese category.4 The rate of obesity among youth has been holding steady at around 17% since 2003–2004.5 The American Cancer Society (ACS) says that one-third of annual cancer deaths in the United States can be attributed to diet and physical activity habits, including overweight and obesity—the same amount caused by exposure to tobacco products.6 Maintaining a healthy weight at every age, or reducing weight when necessary, is clearly an important cancer prevention goal.

How Body Fat Causes Cancer

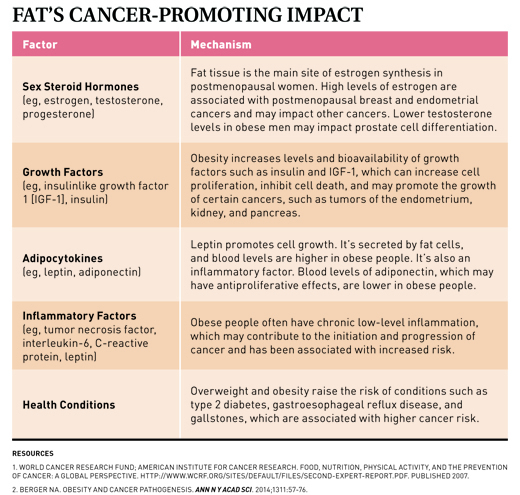

“Body fat doesn’t just sit there,” Bender says. “It’s an active tissue.” According to Marji McCullough, ScD, RD, strategic director of nutritional epidemiology at the ACS and a researcher in the field, a variety of different mechanisms are thought to explain the relationship between excess body fatness and cancer. “Some mechanisms are specific to individual cancers, and some are more general,” McCullough says. “Broadly, excess body fat can influence levels and metabolism of hormones like insulin and estradiol, and it has effects on immune function and inflammation.” Overall, fat tissue activity creates an environment that encourages cell growth and discourages cell death—a perfect environment for cancer.7,8 (See Table “Fat’s Cancer-Promoting Impact” on page 36.)

A good example of the link between excess body fat and cancer is the case of estrogen. After menopause, body fat (adipose tissue) is the main site of estrogen synthesis. Higher estrogen levels increase the risk of hormone-related cancers such as breast and endometrial cancer. In addition, fat cells (adipocytes) produce proinflammatory factors that result in chronic low-grade inflammation, which can promote cancer development.7

Excess body fat, particularly abdominal fat, increases insulin resistance. The pancreas steps up insulin production to compensate, leading to hyperinsulinemia that may raise the risk of certain cancers.7 “Higher insulin levels lead to higher levels of bioavailable IGF-1 [insulinlike growth factor-1],” McCullough says, “which regulates cell proliferation and growth.”

Moreover, the link between body fat and cancer can be secondary to other problems. For example, people who are overweight or obese are at greater risk of conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and gallstones, which increase the risk of esophageal/stomach cancers and gallbladder cancer, respectively.9-11

BMI typically is used to determine what the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) calls “body fatness,” but BMI isn’t the only important measure related to cancer risk. “A higher waist circumference (abdominal obesity) is associated with increased risk of some cancers independent of overall body weight,” McCullough says, “including colorectal and possibly pancreatic, endometrial, and postmenopausal breast cancers. This is because abdominal (visceral) fat is considered more metabolically active than subcutaneous fat.”

Which Cancers Are Linked to Body Fatness?

In August 2016, a working group of the IARC published a report identifying 13 cancers for which they found sufficient evidence linking them to body fatness, up from five in their previous 2002 report.1 In addition, the World Cancer Research Fund and AICR conduct comprehensive ongoing reviews of research on food, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer called the Continuous Update Project. Combining these sources, there’s sufficient and convincing evidence of a link between body fatness and the following cancers.

Blood (Multiple Myeloma)

A 2011 meta-analysis by Wallin and Larsson reported a 15% and 54% higher risk of multiple myeloma mortality in overweight and obese individuals, respectively. The association seems to be particularly strong in women who are overweight from early adulthood. While the mechanism linking BMI to this rare blood cancer is unknown, hypotheses include adipokines such as interleukin-6 in the bone marrow and the effect of IGF-1. Adipose tissue synthesizes interleukin-6, which is considered a potent growth factor in multiple myeloma.12

Brain (Meningioma)

More than one-half of meningiomas express the IGF-1 receptor, and IGF-1 induces the growth of meningioma cells in culture. Since IGF-1 levels increase with body fatness, this is a prime suspect for the mechanism linking weight to these brain tumors. Sex steroid hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, also are suspected of playing a role.13

Breast

Increased levels of estrogen are strongly associated with postmenopausal breast cancer. In postmenopausal women, the main site of estrogen synthesis is fat (adipose) tissue, so increased body fatness increases estrogen levels, and, therefore, breast cancer risk. Conversely, body fatness seems to protect against premenopausal breast cancer.14

Colon and Rectum

Both body fatness and abdominal fatness (independent of BMI) are associated with colorectal cancer—and the higher the BMI or waist circumference, the higher the cancer risk. No one specific mechanism appears to be responsible for this effect, although researchers cite the general cancer-promoting environment encouraged by body fatness.15

Esophagus

While reflux increases the risk of Barrett’s esophagus, a known precursor to esophageal cancer, there’s a link between esophageal adenocarcinoma and obesity even in the absence of reflux. Central obesity (high waist circumference) in particular is associated with increased esophageal adenocarcinoma, even without a high BMI. Laboratory evidence suggests that leptin (found in higher levels in obese individuals) has carcinogenic effects on esophageal cells, and adiponectin (found in lower levels in obese individuals) has anticancer effects.9

Gallbladder

In addition to the general effect of fat tissue contributing to a physiological environment that encourages cancer development and progression, a possible link includes the fact that obesity raises the risk of gallstones, and having gallstones increases gallbladder cancer risk.11

Kidney (Renal-Cell)

The specific mechanisms linking obesity and kidney cancer aren’t clear, but the evidence for a link is considered convincing. Increased insulin levels, high blood pressure, and chronic inflammation all may play a role.16

Liver

In addition to how body fat influences hormones and inflammation, a high BMI is strongly associated with development of type 2 diabetes, which raises the risk of liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). Furthermore, obesity is a risk factor for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). If NASH progresses to cirrhosis, the risk of developing liver cancer increases.17

Ovaries

The mechanisms behind ovarian cancer’s link to excess body fatness are unknown, but the impact of adipose tissue on hormones and inflammatory factors are all thought to play a role.18

Pancreas

Increasing BMI leads to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, both of which increase pancreatic cancer risk.19

Prostate

While the IARC considers data on prostate cancer to be insufficient at this time, both the AICR and the ACS consider it probable that body fatness is linked to risk of advanced or aggressive prostate cancer. As with breast and ovarian cancers, sex hormones may play a central role: Since testosterone plays an important role in prostate cell differentiation, it’s thought that the lower testosterone levels in obese men may lead to the growth of a less differentiated, more aggressive type of prostate cancer.20

Stomach (Gastric Cardia)

A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that obesity is associated with gastric cancer risk, especially in males, and both overweight and obesity were linked with the risk of cancer in the part of the stomach closest to the esophagus—the gastric cardia. Although the mechanism remains unclear, the most widely accepted hypothesis focuses on reflux: Obesity increases intra-abdominal pressure, promoting gastroesophageal reflux. The reflux can lead to Barrett’s esophagus, which is a precursor for gastric cardia cancer.10

Thyroid

Excess body fat throughout adulthood is associated with increased incidence of thyroid cancer and higher thyroid cancer mortality. The thyroid grows larger with increasing body mass. Greater thyroid volume could harbor more cells at risk of becoming cancerous. Hormones such as estrogens, insulin, IGF-1, and cytokines released by adipose tissue (called adipokines) also have been suggested as playing a role in the link between excess body weight and thyroid cancer. In addition, both oxidative stress and the nuclear factor kappa-beta system are affected by obesity and are involved in the development of thyroid cancer.21

Uterus

Increased levels of estrogen are strongly associated with the risk of cancer of the uterine lining (endometrial cancer). Hyperinsulinemia caused by obesity also increases the risk of endometrial cancer, and chronic inflammation is cited as well.22

“At this point, the question isn’t whether being overweight or obese increases cancer risk, but how can we begin to address that issue,” Bender says.

Preventing weight gain is the ideal. “Maintaining a healthy body weight is one of the most critical things we can do to lower our cancer risk,” McCullough says. “The message is to be as lean as possible throughout life without being underweight.”

With regard to cancer, a healthy body weight isn’t just important for prevention. “Eating well, being active, and watching weight matters in terms of chances of survival and avoiding reoccurrence as well,” says Colleen Doyle, MS, RD, managing director of nutrition and physical activity for the ACS. “Watching weight postdiagnosis is critically important, particularly for breast and colorectal cancers.”

Does Losing Weight Help?

“It’s very hard to study the effects of weight loss on cancer risk,” McCullough says, “but some epidemiologic studies indicate that losing weight will decrease cancer risk, particularly for breast cancer.”

Other data are promising as well. “Some research has found a large reduction in cancer risk following bariatric surgery,” Doyle says. Because having more adipose tissue increases certain hormones, inflammatory factors, and other cancer-promoting conditions, decreasing adipose tissue should decrease those levels. “There are conditions we know increase tumor growth, and we see them improving as people lose weight,” Doyle says.

McCullough agrees: “Even modest weight loss improves factors associated with cancer risk, like insulin sensitivity and inflammation, so it seems safe to presume weight loss would be beneficial. Plus, we know it’s important for other conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The ACS guidelines say that losing even a small amount of weight has health benefits and is a good place to start. Even if we don’t have all the data yet, it’s safe to say that if you’re currently overweight, losing weight is a good idea.”

“Of course, you can do all the right things and still get cancer,” Doyle says, “but there’s a lot of evidence [showing] that eating well, being active, and reducing weight can reduce risk.”

What to Do

“We have to increase people’s awareness of the connection between weight and cancer,” Doyle says.

Many people feel there’s little they can do to avoid cancer. “It’s key to let people know that, while there’s no guarantee, there are steps they can take to lower their cancer risk,” Bender says.

Doyle agrees: “The fact that there are things we can control that can reduce our risk is a really empowering message,” Doyle says.

Educating people on behaviors that promote weight loss is a start. “The AICR recommends people try to move more, replace some higher-calorie foods with lower-calorie foods like vegetables, whole grains, and beans, and watch portion sizes,” Bender says. Other recommendations, such as MyPlate, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and guidelines from organizations such as the ACS, American Heart Association, and American Diabetes Association offer similar advice on healthful dietary patterns and habits.

It’s critical to help people achieve the permanent behavior changes that support reaching or maintaining a healthy weight. This can be a complex and long-term process. One way to help foster behavior change is to change the wider environment. “One of the most important recommendations in the ACS guidelines is the recommendation for community action,” Doyle says. “It takes multiple sectors working together to reduce barriers and to create environments conducive to healthful choices. Health professionals, parents, community leaders, politicians … we all need to be advocates for change in our communities.”

Bender adds, “We need to stem the tide of obesity, not just for cancer, but for other chronic diseases as well.”

— Judith C. Thalheimer, RD, LDN, is a freelance nutrition writer, a community educator, and the principal of JTRD Nutrition Education Services, LLC.

WEIGHT AND CANCER PREVENTION

In the United States, maintaining a healthy weight can prevent the following:

- 22% of gallbladder cancers

- 11% of advanced prostate cancers

- 5% of ovarian cancers

- 33% of esophageal cancers

- 19% of pancreatic cancers

- ~24% of kidney cancers

Maintaining a healthy weight and being active can prevent the following:

- 50% of colorectal cancers

- 33% of breast cancers

- 30% of liver cancers

- 59% of endometrial cancers

— Source: American Institute for Cancer Research

References

1. Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Body fatness and cancer — viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794-798.

2. World Cancer Research Fund International. Cancer prevention & survival: summary of global evidence on diet, weight, physical activity & what increases or decreases your risk of cancer. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/CUP-Summary-Report.pdf. Published July 2016.

3. American Institute for Cancer Research. The AICR 2015 cancer risk awareness survey report. http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/education/aicr-awareness-report-2015.pdf

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. DHHS publication 2016–1232.

5. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db219.pdf. Published November 2015.

6. Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30-67.

7. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Second-Expert-Report.pdf. Published 2007.

8. Berger NA. Obesity and cancer pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:57-76.

9. World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and oesophageal cancer 2016. http://wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Oesophageal-Cancer-2016-Report.pdf. Published 2016.

10. Lin XJ, Wang CP, Liu XD, et al. Body mass index and risk of gastric cancer, a meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(9):783-791.

11. World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and gallbladder cancer 2015. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Gallbladder-Cancer-2015-Report.pdf. Published 2015.

12. Teras LR, Kitahara CM, Birmann BM, et al. Body size and multiple myeloma mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(5):667-676.

13. Sergentanis TN, Tsivgoulis G, Perlepe C, et al. Obesity and risk for brain/CNS tumors, gliomas and meningiomas: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136974.

14. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Breast cancer 2010 report: food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of breast cancer 2010. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Breast-Cancer-2010-Report.pdf. Published 2010.

15. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Colorectal cancer 2011 report: food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of colorectal cancer 2011. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Colorectal-Cancer-2011-Report.pdf. Published 2011.

16. World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and kidney cancer 2015. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Kidney-Cancer-2015-Report.pdf. Published 2015.

17. World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and liver cancer 2015. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Liver-Cancer-2015-Report.pdf. Published 2015.

18. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Ovarian cancer 2014 report: food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of ovarian cancer. http://www.aicr.org/continuous-update-project/reports/ovarian-cancer-2014-report.pdf. Published 2014.

19. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Pancreatic cancer 2012 report: food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of pancreatic cancer. http://www.aicr.org/continuous-update-project/reports/pancreatic-cancer-2012-report.pdf. Published 2012.

20. World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity, and prostate cancer 2014. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Prostate-Cancer-2014-Report.pdf. Published 2014.

21. Kitahara CM, McCullough ML, Franceschi S, et al. Anthropometric factors and thyroid cancer risk by histological subtype: pooled analysis of 22 prospective studies. Thyroid. 2016;26(2):306-318.

22. World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Endometrial cancer 2013 report: food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of endometrial cancer. http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Endometrial-Cancer-2013-Report.pdf. Published 2013.