By Cheryl Harris, MPH, RD

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 15 No. 3 P. 42

Linda sat at a table with a piece of rich, dark chocolate in front of her. After breathing in its sweet aroma, she took a small bite and let the chocolate slowly dissolve in her mouth. Her taste buds savored the mixture of creaminess and sweetness. “Wow, that’s the best piece of chocolate I’ve ever eaten!” Linda said to her dietitian.

What’s interesting is that this exchange was part of a nutrition counseling session that focused on mindfulness, the concept of being present in the moment, and mindful eating, being aware of all facets of the eating process. Mindfulness continues to gain widespread support to promote health and wellness, and mindful eating is being used as a tool to improve eating behaviors, encourage weight control, prevent chronic disease, and foster a healthful relationship with food.

Fully Aware

The core principles of mindful eating include being aware of the nourishment available through the process of food preparation and consumption, choosing enjoyable and nutritious foods, acknowledging food preferences nonjudgmentally, recognizing and honoring physical hunger and satiety cues, and using wisdom to guide eating decisions.1

“Either you’re physically hungry or there’s another trigger for eating,” says Megrette Fletcher, MEd, RD, CDE, cofounder of The Center for Mindful Eating. “Mindful awareness helps people notice their direct experiences.”

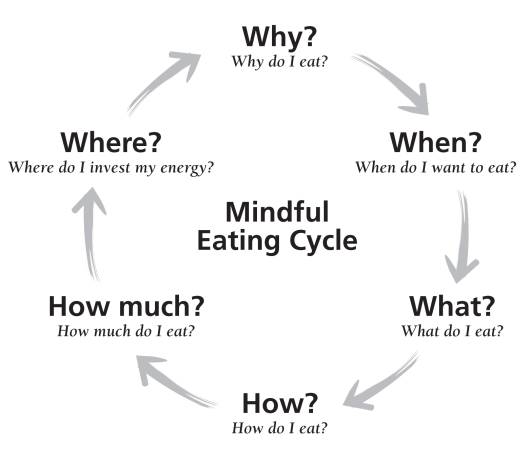

Michelle May, MD, founder of the mindful eating workshops “Am I Hungry?” believes awareness of food and the eating process is a necessary component that facilitates behavior change. “Many of the habits that drive overeating are unconscious behaviors that people have repeated for years, and they act them out without even realizing it,” she says. “The process of mindfulness allows a person to wake up and be aware of what they’re doing. Once you’re aware, you can change your actions.” A visual representation of this eating concept is the “Am I Hungry?” Mindful Eating Cycle (see diagram) from May’s book Eat What You Love, Love What You Eat.

Since most people eat for reasons other than physical hunger, the first question of “Why do I eat?” is often central to ultimately changing behavior.

Since most people eat for reasons other than physical hunger, the first question of “Why do I eat?” is often central to ultimately changing behavior.

• “Why do I eat?” may include an exploration of triggers such as physical hunger, challenging situations, or visual cues, which often spring from stress, fatigue, or boredom.

• “When do I want to eat?” The answer may depend on the clock, physical hunger cues, or emotions.

• “What do I eat?” examines the factors people consider when choosing food, such as convenience, taste, comfort, and nutrition.

• “How do I eat?” Is eating rushed, mindful, distracted, or secretive? In our technological, on-the-go society, exploring the process of eating can be eye-opening.

• “How much do I eat?” Quantity may be decided by physical fullness cues, package size, or habit.

• “Where does the energy go?” Eating may be invigorating, cause sluggishness, or lead to guilt and shame. How is the energy used during work or play?

Nutrition professionals can discuss these and other questions with clients, and encourage clients to ask themselves these questions daily to boost awareness of the factors guiding their eating decisions. “Asking ‘Am I hungry?’ puts a pause between a trigger and a response,” May says. “That gap breaks us out of ineffective, habitual patterns and gives us an opportunity to change old behaviors.”

Ideally, these mindful eating techniques should be used as a framework to give clients additional insight into their eating patterns and not be used as a tool to dictate an appropriate chain of responses. As mentioned, a key component of mindful eating is nonjudgmental awareness of eating patterns. So if the answer to “Why do I eat?” is “Because I’m bored,” there are no rules clients should have to follow commanding which foods are permissible or how much they should eat. Instead, the answers should be viewed simply as information to help clients make informed choices.

Research Behind the Concept

As world-renowned meditation teacher Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, once said, “Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” Research shows how mindfulness benefits patients with cardiovascular disease, depression, chronic pain, and cancer, and studies report decreased stress levels and increased quality of life.2

One of the most researched mindfulness programs is Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). His mindfulness model involves guided mindful meditation practices, gentle stretching, and the discussion of strategies to incorporate mindfulness into daily life. Participants are encouraged to begin meditating daily outside of sessions.

Several other programs have adopted this model to help treat eating disorders such as binge-eating disorder (BED), type 2 diabetes, weight loss, and promote positive dietary changes in cancer survivors. The Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) program by Jean Kristeller, PhD, combines mindful eating experiences, meditation, and discussion on how awareness can help inform participants about their behaviors and experiences surrounding food.3 One study that examined MB-EAT reported that the number of binge-eating episodes among participants decreased from slightly more than four per week to about 1.5, and that many patients no longer met the diagnostic criteria for BED.4 A National Institutes of Health-funded study of 140 subjects who used MB-EAT techniques also experienced reductions in binge-eating episodes and improvements in depression. A third study using MB-EAT that focused on BED and weight loss found that participants with clinical or subclinical BED showed a 7-lb weight loss after 10 sessions.5

MB-EAT was adapted for diabetes patients in a randomized, prospective controlled study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Called MB-EAT-D, the program encouraged participants to combine “inner wisdom,” or mindful self-awareness around food, and “outer wisdom,” or knowledge about nutrition and diabetes concerns. During each session, one group of participants practiced mindful eating exercises and meditation, and was encouraged to continue this at home. They also were taught basic information about nutrition and diabetes. The second group received intensive counseling on diabetes self-management, calorie needs and goals, and exercise.6

Both groups in MB-EAT-D experienced significant weight loss, improved glycemic control, increased fiber intake, and lower trans fat and sugar consumption. There were no significant outcome differences in weight or glycemic control between the two groups, suggesting that mindful eating-based techniques can complement or even provide a viable alternative for diabetes patients.6

In another study, MB-EAT was used to target stress eating and cortisol levels. Obese participants experienced significantly lower cortisol levels and decreased anxiety but had no changes in weight from baseline. However, control subjects gained a significant amount of weight during the study. Patients who reported the greatest reduction in stress also experienced the largest decreases in abdominal fat, which may be useful for lowering risks of metabolic syndrome over time.7

The Mindful Eating and Living Program by Brian Shelley, MD, used the MBSR model. Participants experienced significant weight loss and improvement in mood and inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, after six weeks.8

A 2012 study of prostate cancer survivors showed that a combination of nutrition information, cooking classes, mindfulness, and mindful eating training led to dietary changes linked to lower risk of prostate cancer recurrence. A significant correlation existed between meditation habits at six months and increased vegetable and lower animal product consumption. The authors hypothesized that mindfulness may help support necessary dietary changes in these patients.9

Although mindful eating programs include a meditation component in addition to mindful activities and discussion, others successfully use only hands-on mindful eating exercises. A study that examined mindful eating in restaurants showed a significant reduction in weight, calories consumed, fat intake, and increases in self-confidence among subjects who participated in a six-week mindful eating program.10

Mindful vs. Mindless Eating

While the concept of mindful eating has been shown to be effective and is growing in popularity, so are techniques to reduce mindless eating. The mindless eating concept involves making adjustments to avoid triggers that may compel individuals to eat unhealthful foods, eat too much, or both. Strategies include eating on smaller plates, drinking from smaller cups, repackaging or purchasing single-serving sizes, placing unhealthful foods out of sight, and ordering smaller portions at restaurants.11

“Mindless eating is looking at environmental cues and triggers around eating,” Fletcher says. “Mindful eating is about awareness of internal and external cues that trigger eating.” She adds that the two concepts do overlap when hunger sensations are triggered by the sight or smell of food.

Minimizing mindless eating cues also can make it easier for clients to pay attention to their body’s signals. The popular book Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think by Brian Wansink, PhD, offers great information and many practical strategies to avoid mindless eating.

Where to Begin?

If you’re intrigued by the mindful eating concept and want to discuss it with patients, Fletcher recommends first observing your own eating habits. “Pay attention to your own experiences, and keep asking yourself how this can help your clients, too. Your passion ignites a passion in your patients and makes it much more effective.”

As nutrition professionals, we’re the experts on choosing the quality and quantity of foods needed for optimal health, yet that’s only one piece of the puzzle for many clients. Mindful eating enables you to become more aware of other factors influencing eating decisions, which provides an avenue to empower clients to make the necessary changes from the inside out.

— Cheryl Harris, MPH, RD, is in private practice in Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia. She has a daily meditation practice and uses mindful techniques in client education.

Mindful-Eating Exercises for Clients

Rate Your Hunger

Create a hunger scale ranging from 0 to 10 (0 being the most hungry and 10 being the least hungry).

Ask your client the following questions:

• What does a 0 feel like physically when you’re extremely hungry? (Common answers are headaches, irritation, shakiness, and fatigue.)

• What does a 10 feel like, when you’re as full as you can imagine? (Common answers are nauseous, bloated, fatigued, swollen, accompanied by feelings of shame or guilt.)

• Where are you right now on a scale of 0 to 10? What do you notice about your body that made you choose that number?

Tell the client to keep a journal of his or her hunger rating before, during, and after each meal for three days. The client should note the physical cues that led to the choice of that rating.

Additionally, the client should experiment with eating to achieve a different level of fullness. Ask how the client felt one hour after achieving a hunger level of 6 vs. 8.

Eat a Food Mindfully

Take a raisin, grape, strawberry, piece of cheese, or chocolate.* Observe the appearance and texture. Is there an aroma? What kind of changes do you notice in your body as you observe this food? (Answers may include salivation, impatience, anticipation, and nothing.)

Place a small amount of the food in your mouth, and do not chew it. After 30 seconds (wait 1 minute for chocolate), start chewing.

After your client is finished eating, ask the following questions:

• What did you notice about the flavor or texture before you started chewing the food? After you started chewing?

• How does that compare with your typical experience?

*Some people associate certain foods with feelings of guilt or rules to follow, so ultimately allow clients to choose their own foods.

— CH

Resources

• Eat What You Love, Love What You Eat by Michelle May, MD

• Eat What You Love, Love What You Eat With Diabetes by Michelle May, MD, and Megrette Fletcher, MEd, RD, CDE

• Eating Mindfully: How to End Mindless Eating and Enjoy a Balanced Relationship With Food by Susan Albers, PsyD, and Lilian Cheung, DSc, RD

• Every Bite Is Divine by Annie Kay, MS, RD, RYT

• Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Program That Works by Evelyn Tribole, MS, RD, and Elyse Resch, MS, RD, FADA

• Mindful Eating: A Guide to Rediscovering a Healthy and Joyful Relationship With Food by Jan Chozen Bays, MD

• Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think by Brian Wansink, PhD

• Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life by Thich Nhat Hanh and Lilian Cheung DSc, RD

• The Center for Mindful Eating (www.tcme.org)

References

1. The principles of mindful eating. The Center for Mindful Eating website. http://tcme.org/principles.htm. Accessed December 20, 2012.

2. Praissman S. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: a literature review and clinician’s guide. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(4):212-216.

3. Kristeller JL, Baer RA, Quillian RW. (2006). Mindfulness-based approaches to eating disorders. In: Baer RA, ed. Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Interventions: Conceptualization, Application, and Empirical Support. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2006:75-91.

4. Kristeller JL, Hallett B. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol. 1999;4(3):357-363.

5. Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011;19(1):49-61.

6. Miller CK, Kristeller JL, Headings A, Nagaraja H, Miser WF. Comparative effectiveness of a mindful eating intervention to a diabetes self-management intervention among adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(11):1835-1842.

7. Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, et al. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: an exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes. 2011;2011:651936.

8. Dalen J, Smith BW, Shelley BM, Sloan AL, Leahigh L, Begay D. Pilot study: Mindful Eating and Living (MEAL): weight, eating behavior, and psychological outcomes associated with a mindfulness-based intervention for people with obesity. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(6):260-264.

9. Carmody JF, Olendzki BC, Merriam PA, Liu Q, Qiao Y, Ma Y. A novel measure of dietary change in a prostate cancer dietary program incorporating mindfulness training. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(11):1822-1827.

10. Timmerman GM, Brown A. The effect of a mindful restaurant eating intervention on weight management in women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):22-28.

11. Wansink B. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York, NY: Bantam-Dell; 2006.