March 2016 Issue

March 2016 Issue

Medical and Recreational Marijuana Use

By Liz Marr, MS, RDN, FAND

Today's Dietitian

Vol. 18 No. 3 P. 44

Here's what dietitians need to know plus tips for counseling clients about this fast-growing yet controversial trend.

Sandra, a 35-year-old cancer patient undergoing radiation and chemotherapy, visits her RD to develop meal plans and review her daily nutrient needs. She says she's lost her appetite due to frequent bouts of nausea and vomiting because of her treatment regimen, and she's losing weight. "I heard that smoking medical marijuana can relieve my nausea and vomiting," Sandra says. "I also heard you can eat it in food. Do you know anything about that? I'm considering doing some research on this." Her dietitian's eyes widen. "Well, I've certainly heard about people using it for medical reasons, but I don't think medical marijuana is legal in this state, so I'm not sure I can give you any advice about it."

Like Sandra, more clients and patients are asking RDs about medical marijuana (aka cannabis) to relieve the side effects of chemotherapy treatment and the debilitating symptoms of various other health conditions. And more people are using marijuana recreationally.

An estimated 3% to 5% of the global population aged 15 to 64 (125 million to 227 million people) use cannabis, and North America is the largest market.1 As the number of states allowing medical and recreational marijuana use has increased, more American adults are using it. According to the National Institutes of Health, marijuana use has doubled over the past decade to 1 in 10 adults, and 1 in 5 young adults aged 18 to 29.2

Research shows cannabis plays a beneficial role in pain relief, muscle spasms and seizures, appetite, and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, among other conditions.3,4 However, the therapeutic potential is complicated by the illegal status of cannabis at the federal level, even as states legalize the plant.

With cannabis consumption climbing and state laws rapidly shifting, RDs need to understand its legal and health implications. Boulder, Colorado-based dietitian Donna Shields, MS, RDN, cofounder of the Holistic Cannabis Network, an online cannabis education platform for health professionals, says, "RDs should become educated, especially as cannabis relates to health conditions that are nutrition related."

Deciding how to address cannabis in individual dietetics practice depends not only on the legal overlay, but also on the type of clients RDs typically counsel. For example, dietitians who see patients with cancer may approach cannabis differently from those who work with clients who are in drug recovery. David Wiss, MS, RDN, founder of Nutrition in Recovery in Los Angeles, regularly sees clients who have a history of cannabis dependence. "A large percentage of people can use marijuana recreationally without life impairment, but for some it becomes an addictive substance," Wiss says.

Kelay Trentham, MS, RDN, CSO, an oncology dietitian at MultiCare Regional Cancer Center in Tacoma, Washington, believes consumers benefit from dietitians who are knowledgeable about medical marijuana. "As dietitians, we need to be willing to learn about cannabis so that we can educate patients when they have questions." Of her 11 years in oncology work, Trentham says, "I haven't seen health care providers who are comfortable discussing medical cannabis with patients, until recently. It's either too hard to keep up with the literature when it's outside their specialty, or they have legal concerns. Health care providers need to understand they have a First Amendment right to inform. They cannot obtain, dispense, or write a prescription, but they can discuss potential benefits."

What Is Cannabis?

The Cannabis genus is a dioecious (having male and female seeds), annual, flowering herb that includes several closely related species; the most common are subspecies Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica.5 Psychotropically, sativa typically increases alertness and energy, whereas indica creates a sense of relaxation and, in some cases, lethargy.6 However, plants grown for psychoactive properties have been hybridized repeatedly over the years and today contain varying amounts of both species.

Hemp and marijuana are both popular terms for the cannabis plant. Hemp usually refers to plants or stems with very low levels of psychoactive components, whereas marijuana refers to the dried leaves and flowers of the psychoactive plant varieties.4 Hemp can be used for textiles, biodegradable plastics, and fuel, in addition to food products and dietary supplements.

Like other herbs, but unlike pharmaceutical medications, marijuana isn't composed of a single compound, but rather a complex combination of more than 100 different chemicals, including cannabinoids, flavonoids, and terpenoids.7 The primary psychoactive component of cannabis is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is found in greatest concentrations in the flower buds of female plants. Hemp contains less than 1% THC, whereas levels in psychoactive cannabis range from 4% to as high as 20% in newer varieties.5 (The percent of oils present in a sample of cannabis determines the potency of the psychoactive components.) In addition to THC, there are other therapeutic components such as cannabidiol (CBD), a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid; and arachidonoyl ethanolamide (anandamide), an endogenous ligand that's involved in binding THC and CBD to endocannabinoid receptors, which are found throughout the body.6

History of Cannabis

Both exalted and vilified, cannabis has a long and colorful association with humans. One of the oldest cultivated crops, cannabis evolved in central Asia where human use dates back at least 12,000 years. Barney Warf, PhD, a history professor at the University of Kansas, recently compiled a historical geography of cannabis.5 He indicates hemp and psychoactive marijuana were widely used in ancient China, with the first evidence of medicinal use in 4000 BC. India developed a tradition of psychoactive cannabis cultivation, typically with medicinal and religious ties. Cannabis figured prominently in Ayurvedic medicinal traditions, usually mixed with other herbs.

Warf describes cannabis spreading throughout Europe before medieval times. There, it was used as an alternative to flax and for medicinal purposes until Pope Innocent VIII issued a papal decree in 1484 associating the plant with witchcraft. Recreational cannabis consumption also was widespread throughout the Arabic empire from the seventh to 13th centuries. Arab merchants likely introduced cannabis to Africa, where it diffused throughout most of the continent after the 1100s.

Cannabis came to the New World as part of the Columbian Exchange. According to Warf, indigenous peoples of Latin America, who already used an array of hallucinogens in their culture, easily adopted cannabis as a psychotropic agent. He indicates the British pursued hemp production for use in sails, rope, nets, paper, clothing, and sacks to reduce reliance on Russian sources. Thus, during British colonial times, farmers in the Jamestown colony were required to grow hemp. In the United States, hemp production decreased after the Civil War. Cannabis appeared in the US Pharmacopoeia from 1851 to 1942, and was available in many drug stores up until the 1930s.8

Regulatory Frameworks in the United States

Warf notes that unlike Prohibition, which restricted only the manufacture and distribution of alcohol, federal marijuana laws have consistently outlawed production, sale, possession, and consumption. In addition, he says that American laws have blurred the lines between hemp and marijuana, in part, due to historic opposition from cotton growers, who feared competition from hemp. The temperance movement also played a part in 29 states outlawing the plant by 1931.5,9 Many prejudices against marijuana spread through anti-immigrant and racially based public discourse, according to Warf. Embedded in this history is the federal government's choice to use the term marijuana (from Latin American Spanish) or historically, marihuana, over the botanical term cannabis. In 1937, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, effectively criminalizing possession.5

Except for a brief interlude during World War II, when hemp was legal for war purposes, cannabis has since remained illegal at the federal level. In 1951, Congress passed the Boggs Act, giving marijuana and heroin possession the same penalties.9 Widespread cannabis use during the 1960s, including significant numbers of youth, led to the passage of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970.5 The act established the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, which concluded in 1972 that the actual and potential harm wasn't great enough to justify criminalization.9 The commission's recommendation to decriminalize cannabis was ignored by both President Richard Nixon and Congress. Since the passage of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, the federal government has classified marijuana (including hemp plants) as a Schedule I controlled substance along with heroin and LSD "with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse."10 However, in 2014 Congress passed legislation prohibiting the Department of Justice from interfering with states that have legalized hemp or medical cannabis.11

With the passage of Proposition 215 in 1996, California became the first state to allow the medical use of marijuana.12 Since then, 22 more states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico have enacted laws establishing comprehensive public medical marijuana and cannabis programs.8

An additional 17 states allow use of low-THC, high-CBD products for medical reasons.12 Four states plus the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana for recreational use (see Table 1).13

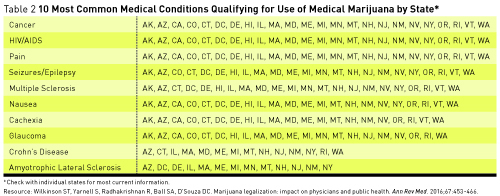

The 24 states, including the District of Columbia, that have legalized medical marijuana have done so for the following, most common health conditions: cancer, HIV/AIDS, and pain (all states); seizures/epilepsy (23 states); nausea and multiple sclerosis (22 states); glaucoma and cachexia (21 states); Crohn's disease (14 states); amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (13 states); hepatitis C (12 states); agitation in Alzheimer's (11 states); posttraumatic stress disorder (8 states); Parkinson's disease (5 states); and arthritis (3 states) (see Table 2).7

Therapeutic Cannabis

Because of the federal government's classification of marijuana as a Schedule I substance, biomedical research has been limited. According to Trentham, the illicit nature of marijuana has skewed research endeavors, in that the "availability of funds and product has more often than not been based on research to study harmful effects" vs efficacy for various health conditions. In fact, several leading medical organizations, such as the American Medical Association (AMA), American Academy of Family Physicians, and American Academy of Neurology, have recommended federal policy be reexamined to allow for research on the potential therapeutic uses of marijuana.3,14,15 The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics doesn't have a position on medical marijuana; however, several medical groups, including the AMA and American Academy of Pediatrics, have addressed the topic in technical reports and policies.3,6,14,15

In the United States, two cannabinoids in pill form (dronabinol and nabilone) have been FDA approved specifically for nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy in cancer treatment and for appetite stimulation in wasting illnesses such as HIV infection and cancer.16 Aside from these two FDA-approved indications, evidence supporting medical use of marijuana and cannabinoids varies widely by disease. A recent meta-analysis of 79 randomized clinical trials including 6,462 participants concluded that there's moderate-quality evidence to support the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pain and multiple sclerosis-related spasticity, and low-quality evidence suggesting that cannabinoids are associated with improvements in nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, weight gain in HIV infection, sleep disorders, and Tourette syndrome.16 Another systematic review found efficacy or probable efficacy for multiple sclerosis-related spasticity, central pain, and reducing bladder void; probable ineffectiveness for levadopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson disease; and unknown efficacy for Huntington disease, Tourette syndrome, cervical dystonia, and epilepsy.3

Since cannabis is a plant, concentrations of various cannabinoid compounds vary substantially, making it difficult to characterize specific health effects.7 Moreover, the average THC concentration in marijuana has increased from 1% to 9% in the past three decades, meaning that older studies may be inapplicable today.5 More research is needed, given rapidly changing legalities, increased potency, and broader usage.

Potential for Misuse and Nutrition Implications

Another important issue is that cannabis consumption can produce short-term and long-term adverse effects. The most common acute adverse effects are dizziness, dry mouth, nausea, fatigue, somnolence, euphoria, vomiting, disorientation, drowsiness, confusion, loss of balance, and hallucination.7

Long-term consumption can lead to cannabis dependence, although the research on physical vs psychological dependence is mixed. Up to 30% of regular cannabis users develop dependence.2 However, the lifetime risk of developing dependence among those who have ever used cannabis was estimated in the 1990s to be at 9% compared with 32% for nicotine, 23% for heroin, 17% for cocaine, 15% for alcohol, and 11% for stimulants.16 Cannabis smoking likely increases cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged adults, but effects on respiratory health remain unclear, primarily because most cannabis smokers are former or current tobacco smokers.17

Since 2002, there has been an increase in marijuana dependence and abuse.2 Thus, dietitians may be more likely to see clients for whom cannabis consumption is problematic. As mentioned, it depends on the area of practice. Because Trentham sees cancer patients, some of whom may have a poor prognosis, she isn't as concerned about clients developing a dependence on cannabis. She says her patients typically are rare or never users and seem likely to revert back to that after treatment.

On the other hand, Wiss sees clients "who are trying to stop marijuana consumption, often for the sixth, seventh, or eighth time." He says published research about the nutrition implications of substance abuse is lacking; therefore, much of his perspective has developed from clinical experience. Wiss, who sees some clients "who have never cooked [meals] or have little shopping experience," says they have what he calls one of the biggest barriers to stopping marijuana use: poor life skills, which can impede clients' ability to achieve sobriety. So his Nutrition in Recovery team not only conducts nutrition education, but also cooking classes and shopping tours. Of the relationship between marijuana and food, Wiss has observed a cycle with his clients. He says, "In early stages, a person may get stoned" and experience "the munchies and increased eating. But after chronic use, the appetite-stimulating effect of marijuana declines. Marijuana is expensive, and those who are dependent on it may have fewer resources available for food, and less motivation to fix food." Wiss also has observed that chronic marijuana smoking, like cigarette smoking, damages taste perception, with the result that both types of smokers "almost always have a preference for higher salt, higher sugar foods."

Moreover, Wiss says that among his clients with eating disorders, addiction rates of various substances are higher in binge eaters vs those with anorexia or restrictive bulimia. In his clinical opinion, Wiss says, "Substance abuse is invariably a barrier to regaining peace with food and body."

Edibles and Other Ingestion Routes

Consumption methods of medical or recreational marijuana use have varied over the centuries. However, today, marijuana is most commonly smoked, either in pipes or as joints or blunts (hand-rolled cigarettes or cigars). In an effort to avoid potentially harmful byproducts in smoke, some consumers have turned to cannabis vaporizers—known as vaping.18 Although vaping may theoretically allow consumers to avoid the inhalation of carcinogens associated with smoke, rigorous clinical studies confirming safety are lacking.19

Trentham recognizes that patients who smoke or vaporize medical cannabis usually have smoked it recreationally in the past. Both Trentham and Shields say people new to medical cannabis are likely to start with cannabis-containing foods or beverages called edibles. And this can be problematic on several fronts. When smoked, THC is rapidly absorbed, producing effects within minutes. With edibles, onset and duration of effects may be longer and irregular. So while consuming edibles may feel more comfortable psychologically, the effects may overwhelm people who are cannabis naïve. The level of cannabinoids in different edibles varies. Further, the form of the edible as well as the presence of other foods can impact onset and duration. "Edibles have received bad press because people don't understand the nuances, and they tend to overconsume," Shields says. In addition, concerns have been raised about children accidentally consuming edibles, confusing them with regular foods and beverages.

The nutritional content of edibles also is a consideration. Because THC is fat soluble and must be heated to be psychoactive, edibles typically are high-fat baked goods, such as cookies and brownies, or candies, like chocolates and caramels. Sweetened beverages, for example, Canna Cola and Dixie Elixirs, are another popular form. Shields sees a need for edibles with more healthful nutrition profiles, and Holistic Cannabis Network plans to launch a healthful brand of edibles in Colorado.

Branded edibles normally are labeled as dietary supplements and sometimes contain added vitamins. However, technically the FDA doesn't allow CBD products to be marketed as dietary supplements.20

Of particular concern is the ongoing potential for inaccurate labeling regarding the psychoactive components of edibles. In February 2015, the FDA issued warning letters to several companies concerning marketing unapproved drugs.21 Some of these firms claimed that their products contain CBD; however, the FDA tested the products and, in some cases, did not detect any of the substance. In one study, researchers analyzed samples of 75 edible products purchased from August through October 2014 in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle.22 Despite state regulations, labeling inaccuracies were found on the majority of the products: 23% were underlabeled, and 60% were overlabeled with regard to THC content. Such inaccuracies lead to inconsistent consumer experiences, including possible adverse or lack of desired effects. It's important to note that labeling regulations and oversight vary from state to state.

According to Shields, for "those with medical concerns who need to be pretty spot-on with dosing," cannabis-infused tinctures may be helpful. Using tinctures, a microdose can be placed under the tongue or added to beverages.

Additional products include other concentrates, such as hash (resin collected from the cannabis flower, in forms such as wax, shatter, and oil) and kief (trichomes, the crystals that coat the outside of the flower bud). Wiss is concerned about the drug-culture aspects of consuming certain concentrates via glass pipes as well as the potential for increased tolerance.

Given the lack of federal oversight, Trentham cautions patients to ask dispensaries about lab testing to validate levels of pharmacologically active ingredients. She further suggests people ask how the product is grown, including use of fertilizers and pesticides. Some grow operations claim organic production methods, but unlike organic foods, use of the term "organic" for cannabis production is unregulated.

Bioethical Considerations for Dietitians

Trentham, who is chair-elect of the Academy's Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group, presented at the Academy's Food & Nutrition Conference & Expo® in Nashville in October 2015, about bioethical considerations for dietitians concerning medical cannabis and oncology patients. She says that because cannabis has been embedded in American counterculture, RDs may have their own biases, both positive and negative. "For many, the immediate gut response may be, 'this is illegal, illicit,'" she says, "but dietitians must overcome their own biases to help patients." Pointing to the principles of providing benefit, doing no harm, and respecting patient autonomy, Trentham says if dietitians have qualms they should apply bioethics principles and those specific to cannabis and their client base when discussing medical marijuana use.

Tips to Address Cannabis Use in Practice

RDs often are among the few clinicians on the health care team that patients will talk to about alternative therapies, which places dietitians in a unique position to counsel them about medical cannabis, Trentham says. She suggests dietitians ask patients whether they're using any vitamins, supplements, or botanicals. If they don't mention marijuana, ask, "Are you using or have you considered using medical cannabis?"

Wiss notices treatment for addiction and eating disorders becoming more integrated; this will make dietitians a more critical part of the health care team and lead to improved patient care. For dietitians working with patients who have eating disorders, he says it's imperative to screen for alcohol, marijuana, and use of other substances to rule out or address dependence.

According to Shields, "Therapeutic cannabis should not be considered in isolation, but rather as part of a holistic lifestyle that includes diet, meditation, and exercise." The Holistic Cannabis Network is offering a free online education event called the Holistic Cannabis Summit, April 4-7, 2016, targeting allied health professionals, patients, policy makers, and members of the cannabis industry.

Trentham offers the following key points for dietitians related to medical cannabis:

• Be familiar with the law, not just at the state level but also locally, to help keep patients informed.

• Review the scientific literature to understand and have the ability to describe the efficacy and pharmacokinetics of cannabis.

She hopes more RDs will become interested in gaining knowledge about medical cannabis: "RDs have more time than doctors. If we become more educated and can address medical cannabis from an evidence-based perspective, we may become more valuable to both patients and the health care team."

— Liz Marr, MS, RDN, FAND, is a writer, recipe developer, and nutrition communications consultant located in Boulder County, Colorado.

[Sidebar]

RESOURCES

The following resources may be useful for dietitians interested in addressing recreational or medical cannabis in their practice.

• Backes M. Cannabis Pharmacy: The Practical Guide to Medical Marijuana. New York; NY: Black Dog & Levanthal; 2014.

• Holistic Cannabis Network: holisticcannabisnetwork.com

• International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines, Clinical Studies and Case Report Database: cannabis-med.org/studies/study.php

• Jonsen A, Siegler M, Winslade W. Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical; 2010.

• United Patients Group: unitedpatientsgroup.com

References

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report 2014. https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2014/World_Drug_Report_2014_web.pdf. Published 2014.

2. Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235-1242.

3. Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1556-1563.

4. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456-2473.

5. Warf B. High points: an historical geography of cannabis. Geogr Rev. 2014;104(4):414-438.

6. Ammerman S, Ryan S, Adelman WP. The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e769-e785.

7. Wilkinson ST, Yarnell S, Radhakrishnan R, Ball SA, D'Souza DC. Marijuana legalization: impact on physicians and public health. Ann Rev Med. 2016;67:453-466.

8. Hermes K. World's leading experts issue standards on cannabis, restore classification as a botanical medicine. Americans for Safe Access website. http://www.safeaccessnow.org/world_s_leading_experts_issue_standards_on_cannabis. Published December 11, 2013.

9. Report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse: marihuana: a signal of misunderstanding. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy website. http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/studies/nc/ncmenu.htm

10. Drug scheduling. US Drug Enforcement Administration website. http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml

11. President signs federal spending bill protecting state sanctioned medical marijuana programs. NORML website. http://norml.org/news/2014/12/18/president-signs-federal-spending-bill-protecting-state-sanctioned-medical-marijuana-programs. Published December 18, 2014.

12. State medical marijuana laws. National Conference of State Legislatures website. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Updated January 25, 2016.

13. Legalization. NORML website. http://norml.org/legal/legalization

14. H-95.952. Cannabis for medicinal use. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/ssl3/ecomm/PolicyFinderForm.pl?site=www.ama-assn.org&uri=/resources/html/PolicyFinder/policyfiles/HnE/H-95.952.HTM

15. Marijuana. American Academy of Family Physicians website. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/marijuana.html

16. Hill KP. Medical marijuana for treatment of chronic pain and other medical and psychiatric problems: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2474-2483.

17. Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction. 2015;110(1):19-35.

18. Lee DC, Crosier BS, Borodovsky JT, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. Online survey characterizing vaporizer use among cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;159:227-233.

19. Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015;110(11):1699-1704.

20. FDA and marijuana: questions and answers. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm421168.htm. Updated September 30, 2015.

21. Warning letters and test results. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm435591.htm. Updated August 5, 2015.

22. Vandry R, Raber JC, Raber ME, Douglass B, Miller C, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2491-2493.