Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18 No. 9 P. 24

Some of Your Most Pressing Questions Answered

The FDA recently announced updates to the Nutrition Facts label.1 The sweeping changes are the first of their kind since Nutrition Facts labels started appearing on food packages in 1993. The hot topics have included the addition of added sugars, vitamin D, and potassium to food labels, as well as changes to serving sizes to more accurately reflect how much we’re eating at one time. Since the changes were announced, questions have surfaced about many of the updates. (The author has been published on this subject; a summary of all the major changes can be found in “The New Food Label: What RDs Need to Know” on Today’s Dietitian‘s website.)2 The following questions and answers relate to how the DVs changed and why total fat was increased.

Q: What do DV and %DV mean, and how are these values changing on the updated food label?

A: DV on food labels is a generic term the FDA developed to reflect different sets of nutrient intake values. DVs are based on two sets of nutrient intake values: Daily Reference Values (DRVs) and Reference Daily Intakes (RDIs). DRVs apply to total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, total carbohydrate, dietary fiber, sodium, potassium, and protein. RDIs apply to vitamins and minerals, protein for children younger than age 4, and for pregnant women and lactating women. To avoid having to list both “%DRV” and “%RDI” on food labels, the FDA uses %DV for all nutrients. The %DV on the label reflects the percentage of a particular nutrient in one serving of a product, based on the daily recommended intake level (either DRV or RDI) for that specific nutrient.

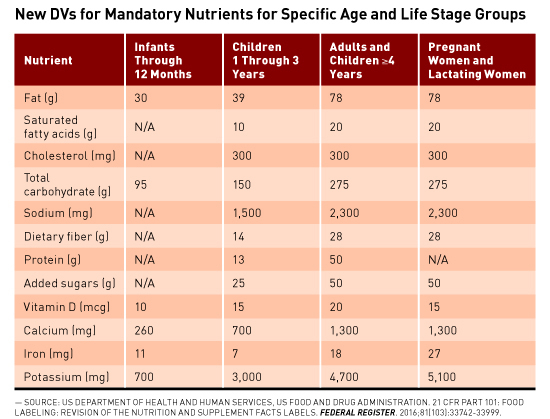

In 2016, the FDA updated the DVs for certain mandatory and voluntary nutrients declared on the food label and developed new DVs (based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine and Dietary Guidelines for Americans) for “added sugars,” infants to 12 months of age, children aged 1 to 3, and pregnant women and lactating women. This means that, on food labels for foods such as infant rice cereal and toddler meals, %DVs will reflect nutrient intake recommendations for these specific age and life stage groups. While the actual food labels will look the same, the %DVs will be based on different amounts specific for these subpopulations. For all other foods such as bread, cheese, and other packaged foods, the %DVs will be based on nutrient intake recommendations for children and adults aged 4 and older. See the table for the new DVs for these subpopulations. For a full list of the new mandatory and voluntary DVs for all age groups and life stages, see tables 4 and 5 in the Federal Register.1

Trans fat and sugar (total) don’t have a %DV listing on Nutrition Facts labels because there’s no reference value (ie, no recommended intake level) on which to base a %DV calculation. Protein also typically doesn’t have a %DV declaration because a %DV for protein is only required if a claim is made about protein, such as “high in protein,” or if the food is marketed for infants and children younger than age 4 to consume.

Percent DV on food labels can be used to find foods that are high or low in certain nutrients and quickly compare different products to find more healthful options. When trying to quickly assess products, clients can keep in mind the following: The FDA considers 5% DV or less per serving to be low and 20% DV or more per serving to be high.

Q: Why did the FDA increase the DV for fat?

A: While the 2014 proposed rule outlining changes to Nutrition Facts labels didn’t recommend changing the DV for total fat, the FDA announced in the final rule an updated DV for total fat, increasing it from 30% of kcal to 35% of kcal (increasing the DV from 65 to 78 g). The FDA revised its position in the final rule to support current dietary recommendations and clinical guidelines suggesting that the types of fat we eat are more important in determining the risk of heart disease than is total fat intake. This is largely based on the conclusion of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) that consistent evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fats, such as polyunsaturated and to a lesser extent monounsaturated fats, significantly reduces total and LDL cholesterol.

The Institute of Medicine set the recommendation for total fat intake using an acceptable macronutrient distribution range (AMDR). The AMDR for total fat intake is 20% to 35% of kcal for adults and 25% to 35% of kcal for children aged 4 to 18. While the proposed rule stated that the upper level of the AMDR (35% of 2,000 kcal) would provide no meaningful health benefit, after reviewing the evidence from the 2015 DGAC, the FDA changed its stance. In the final rule, the FDA also stated concern that consumers might think a total fat DV of 30% of kcal meant to limit total fat intake to 30% or less, and could lead consumers to misinterpret foods that are good sources of mono- and polyunsaturated fats as bad since their %DV for total fat would be high. Thus, the FDA increased the DV for total fat to reflect the upper end of the AMDR, 35% of kcal. Given that the average fat intake for Americans aged 2 and older is about 80 g per day,3 the amount of fat consumers are eating already seems to coincide with the upper end of the range.

Importantly, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are voluntary nutrients on the food label, so manufacturers don’t have to label them unless they choose to do so. In addition, since there’s no recommended intake level for either nutrient, even if labels do include these two nutrients, they won’t have a nutrient content claim (such as “good source of polyunsaturated fatty acids” or a %DV listing. Dietitians can help their clients choose foods higher in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids by identifying food groups such as nuts and seeds including walnuts, macadamia nuts, and sunflower seeds, tofu, soybeans/soybean oil, and fatty fish such as salmon, herring, and trout.4

— Jessica Levings, MS, RDN, is a freelance writer and owner of Balanced Pantry, a consulting business that helps companies develop and modify food labels, conduct recipe analyses, and create nutrition communications materials. Learn more at www.balancedpantry.com, Twitter @balancedpantry, and Facebook.com/BalancedPantry1.

References

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration. 21 CFR Part 101: food labeling: revision of the nutrition and supplement facts labels. Federal Register. 2016;81(103):33742-33999.

2. Levings J. The new food label: what RDs need to know. Today’s Dietitian website. http://www.todaysdietitian.com/enewsletter/enews_0516_03.shtml. Published May 2016. Accessed June 12, 2016.

3. US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. What we eat in America, NHANES 2011–2012. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/80400530/pdf/1112/Table_1_NIN_GEN_11.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2016.

4. Polyunsaturated fats. American Heart Association website. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/FatsAndOils/Fats101/Polyunsaturated-Fats_UCM_301461_Article.jsp#.V6iku5MrJEI. Updated October 7, 2015. Accessed June 12, 2016.