Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 10, P. 16

The answer isn’t so simple.

The effect of dietary fats on the risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) has been studied, discussed, and dissected for decades, but only recently have experts begun to understand just how complex the interactions among these nutrients can be, especially when it comes to the balance of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids.

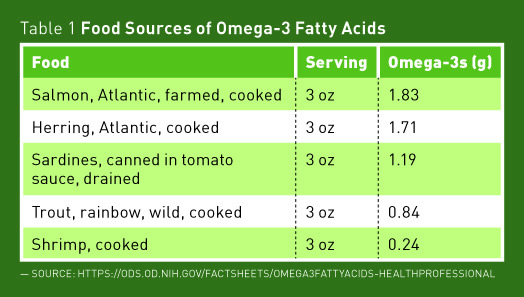

It’s generally accepted that saturated fats, which were identified as contributors to CHD more than 50 years ago, should be minimized in the diet. The current recommendation from the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans is to keep saturated fats to less than 10% of total calories.1 There’s no argument that artificial trans fats in processed foods are bad for heart health, and, as of June 2018, the FDA no longer will allow them to be added to processed foods.2 Experts overwhelmingly agree that omega-3 fatty acids, the kind found in fatty fish, canola oil, walnuts, and flaxseeds, reduce inflammation and benefit overall health. The Adequate Intake for omega-3s has been established at 1.1 g/day for women and 1.6 g/day for men.

There’s far less agreement, however, when it comes to intake of omega-6 fatty acids, especially the question of what the ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s should be in the diet.

Omega-3s vs Omega-6s

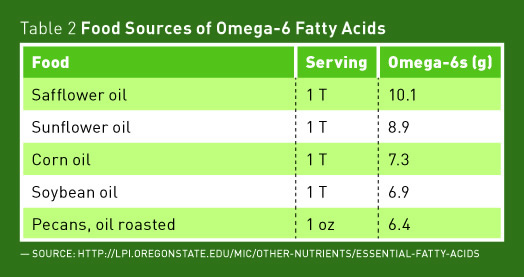

It’s believed that human beings evolved on a diet with a ratio of about 1:1 omega-6s to omega-3s, but that’s no longer the case.3 The average American’s diet now contains far more omega-6s than omega-3s. Linoleic acid (LA) is an essential polyunsaturated fatty acid that makes up as much as 90% of the dietary intake of omega-6 fatty acids in the United States.4 Though no specific requirement has been set for omega-6s, an intake of 0.5% to 2% of calories is thought to be sufficient to meet needs. The Adequate Intake level for LA has been set as 17 g/day for men and 12 g/day for women (5% to 6% of calories).4 Based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the average intake of someone on a 2,000-kcal diet is more than that—around 6.7% of calories.4 Concerns have been raised about getting too much of a good thing because the body has the ability to convert LA to arachidonic acid, which can then be converted to several proinflammatory molecules, including thromboxane A2 and leukotriene B4. The theory has been that getting too much omega-6s relative to omega-3s could lead to inflammation, CHD, and an increased risk of death.

Several rodent studies have suggested that this is the case.5 However, it also has been found that mice handle polyunsaturated fatty acids quite differently than humans, bringing the findings into question.6 Some population studies have suggested that an unbalanced ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s in the diet is detrimental to health and have found it to be associated with an increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, CVD, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, and even Alzheimer’s disease.5,7 Some researchers go so far as to state that a lower ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids is needed for the prevention and management of chronic disease, but there’s little direct evidence to support the connection between omega-6 intake and inflammation or disease. Even if that were proven to be the case, genetic variations among individuals would make it impossible to determine the optimal ratio for any individual or for the disease in question.8

To further complicate the omega-6/omega-3 connection, several studies have found the opposite to be true (ie, higher levels of omega-6s may be beneficial).9,10 One review and analysis of randomized controlled trials found that consuming polyunsaturated fats such as LA in place of saturated fats significantly reduced CHD events.11 A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies also found dietary intake of LA to be inversely associated with CHD risk. The association was dose dependent—the greater the intake of omega-6s, the lower the risk.10 In addition, research has found that higher serum levels of omega-6s are associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes,12 and a study of elderly Swedish men found that the greater the level of LA in fat tissue, the lower the mortality rate over almost 15 years.13

Competition between LA and alpha-linoleic acid (ALA) for the same conversion enzymes also plays a role in the omega-3/omega-6 ratio in the body. ALA is an essential omega-3 fatty acid found primarily in plant foods such as flaxseed oil, canola oil, and English walnuts. The omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, which have been associated with decreased risk of CHD and inflammation, can be synthesized from ALA, but due to an inefficient conversion process and competition with LA for the same conversion enzymes, it’s recommended that EPA and DHA be obtained directly from foods, particularly fatty fish such as salmon, sardines, and trout.14

Making Sense of Mixed Messages on Omegas

While the research regarding the ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s is inconsistent, the message from the American Heart Association (AHA) is clear—aim for an intake of omega-6 polyunsaturated fats of at least 5% to 10% of calories, along with other AHA lifestyle and dietary recommendations. The official position of the AHA is as follows: “To reduce omega-6 [polyunsaturated fatty acid] intakes from their current levels would be more likely to increase than to decrease risk for CHD.”4 Adequate intake of both omega-6s and omega-3s are essential for good health and low rates of chronic disease, but at this point an optimal or detrimental ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s can’t be identified.

— Densie Webb, PhD, RD, is a freelance writer, editor, and industry consultant based in Austin, Texas.

References

1. US Department of Health & Human Services; US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Eighth Edition. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/. Published January 7, 2016.

2. Final determination regarding partially hydrogenated oils (removing trans fat). US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/food/ingredientspackaginglabeling/foodadditivesingredients/ucm449162.htm. Updated June 20, 2017. Accessed July 28, 2017.

3. Simopoulos AP. Evolutionary aspects of diet, the omega-6/omega-3 ratio and genetic variation: nutritional implications for chronic diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60(9):502-507.

4. Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, et al. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009;119(6):902-907.

5. Simopoulos AP. An increase in the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):128.

6. Fritsche KL. The science of fatty acids and inflammation. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(3):293S-301S.

7. Patterson E, Wall R, Fitzgerland GF, Ross RP, Stanton C. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:539426.

8. Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008;233(6):674-688.

9. Farvid MS, Ding M, Pan A, et al. Dietary linoleic acid and risk of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation. 2014;130(18):1568-1578.

10. Poli A, Visioli F. Recent evidence on omega 6 fatty acids and cardiovascular risk. Euro J Lipid Sci Tech. 2015;117(11):1847-1852.

11. Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252.

12. Yary T, Voutilainen S, Tuomainen TP, Ruusunen, Nurmi T, Virtanen JK. Serum n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, Δ5- and Δ6-desaturase activities, and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Factor Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(5):1337-1343.

13. Iggman D, Ärnlöv J, Cederholm T, Risérus U. Association of adipose tissue fatty acids with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in elderly men. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(7):745-753.

14. Essential fatty acids. Oregon State University, Linus Pauling Institute, Micronutrient Information Center website. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/other-nutrients/essential-fatty-acids#food-sources