Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 10, P. 20

These 10 strategies will help RDs meet the nutrient needs of this unique population.

With rising interest in plant-based diets, encountering a vegan or vegan-curious client no longer is a rarity. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has long recognized appropriately planned vegan diets as healthful and nutritionally adequate for individuals of all ages throughout the lifecycle, and vegetarians and vegans have been the subject of long-term epidemiologic study for decades. In the midst of epidemics of heart disease, stroke, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, long-term prospective studies and clinical trials consistently find that plant-based vegan diets show significant promise in preventing, addressing, and mitigating cardiometabolic risk factors.1-4

In my experience working with vegans over the past 14 years, I’ve found these clients to be knowledgeable and motivated to adopt a plant-based eating pattern and look for the direction and expertise dietitians are trained to provide. This article will help dietitians understand the motivations of these clients, address potential fears and barriers to working with them, and give RDs evidence-based resources they can use for effective counseling sessions.

1. Know the Type of Vegetarian or Vegan You’re Counseling

First, dietitians need to know which foods are acceptable to clients and which aren’t. A vegetarian eats no flesh foods, including fish and chicken, but does eat eggs and dairy. Vegans, on the other hand, eat no animal foods, so eggs and dairy and their byproducts, such as egg whites and whey, all are off limits. But that’s not the end of it. For ethical vegans, clothing, soap, and beauty products that contain animal products also are excluded. In some cases, vegans may avoid restaurants where meat is served.

Another related dietary pattern is called Whole Foods Plant Based, or WFPB for short. Motivated by health, WFPB advocates avoid not only animal products but also refined foods such as white rice, white bread, and vegetable oils. The focus is squarely on the benefits of whole plant foods. These clients are extremely motivated by health—and most WFPB clients I’ve worked with are knowledgeable about nutrition. The diet is stricter than veganism in many ways, which can make eating out difficult, even at vegetarian restaurants. Sometimes WFPB is known simply as “plant-based,” but there’s some confusion because the term also is used interchangeably with flexitarian, a person who often, but not exclusively, eats vegetarian meals.

2. Understand Their Motivations

On paper, it may seem as though eating in such a restrictive manner would be unsustainable and the motivation to do so would eventually wane. It’s true that a vegan dietary pattern takes extra motivation, as do most dietary behavior changes, because unhealthful eating is normalized in Western society. But don’t underestimate the convictions of the vegan or vegan-curious client. Some, like the WFPB crowd, are extremely motivated to reduce their risk of chronic diseases through diet. They’re ahead of the curve, so to speak, as consumption of plant foods is associated with improved health outcomes, and this thinking should be encouraged.

Ethical vegans aren’t motivated by improving their own health as much as by boycotting the use of animals for food. The choice to exclude animal foods is one based on the moral principle that animals have their own lives and the purpose of their existence isn’t to feed humans. This ethical concern for other species isn’t new; philosophers as far back as Pythagoras have questioned the use of animals on moral grounds. “Why love one, but not the other?” they may ask, with regard to a companion dog or cat.

These ideas aren’t mainstream, but it’s estimated that 3.7 million people in the United States consider themselves vegan,5 an approximate 700% increase from 1994.

This motivation for dietary change is strong, especially in young people, who are more likely to be political in ways related to their personal behavior. I advise RDs to recognize this motivation and guide new vegans to the foods they need that fit within the parameters they’ve set. It’s a unique opportunity to have a client who’s motivated to eat more fruits and vegetables.

When collecting information from clients before their first visit, inquire about the books they’ve read and MDs and RDs they follow.

3. Build Rapport and Trust

Vegan clients may have a distrust of health professionals because the idea that animal-based industries influence the fields of nutrition and medicine is prevalent.

What’s important here is that these clients have trusted you to help them understand their nutritional needs. Showing them that you understand their motivations—even if you don’t share the same belief system—can go a long way in knocking down barriers and improving health outcomes. Ideas about nutrition that aren’t evidence based may be tied in with this belief system and should be approached carefully.

Kayli Dice, MS, RD, director of nutrition and health care at Lighter, an online community that helps people eat more healthfully across the country through meal recommendations, menu creation, and grocery shopping advice, says she addresses this by “asking a lot of questions to understand where their belief came from and why it feels important to them, and then I help them understand the science (or, more likely, the lack of science) behind any nutrition myths.”

4. Use Evidence-Based Resources

The Academy’s position paper on vegetarian diets states that vegan diets are appropriate for the entire life cycle and that research suggests they’re beneficial in reducing the risk of CVD.6 In addition, several plant-based and vegan RDs have websites and books outlining the evidence along with meal plans and nutrient sources (see sidebars).

5. Learn About Vegan Clients’ Resources

Is prepared or store-bought vegan food readily available in their neighborhood? Do they have experience cooking and preparing plant foods? Are they ready to implement the changes they’re inspired to make?

During counseling sessions, dietitians have only a short period of time to measure their willingness to change and provide adequate resources. Meeting nutrient needs when following a vegetarian or vegan diet doesn’t require much money or demand excessive preparation. However, as with almost all healthful eating plans, following these eating patterns does take some combination of the two. A homemade bean and rice burrito can cost less than $1, while an organic, freshly pressed juice can cost upwards of $20.

Knowing whether clients prefer to cook at home or can afford to eat out will help you better counsel them. Many of Dice’s clients who considered themselves skilled cooks suddenly felt lost in the kitchen as new vegans.

“After learning new skills like various ways to prepare and season vegetables, and some experimentation with new ingredients, cooking and assembling vegan meals becomes intuitive,” Dice says. “I’ve seen roasted Brussels sprouts change the game for many self-proclaimed Brussels sprouts haters!”

6. Keep It Simple

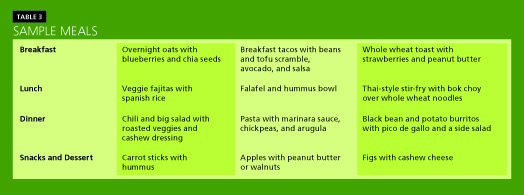

I’m an advocate of the grain-bean-vegetable-sauce method of food preparation. Many cultures around the world eat similarly, from falafel patties on rice with tomatoes and tahini sauce to pad kee mao with noodles, tofu, and Chinese broccoli. Contemporary vegan bowls can include quinoa with chickpeas, kale, and a sesame seed sauce, or wild rice with roasted peppers, onion, and spinach with a peanut sauce. Breakfast foods also can mimic this pattern. Clients can replace vegetables with fruit and prepare overnight oats with blueberries, walnuts, and almond milk, or peanut butter and strawberries on toasted whole wheat bread.

7. Think Outside the Box to Meet Nutrient Needs

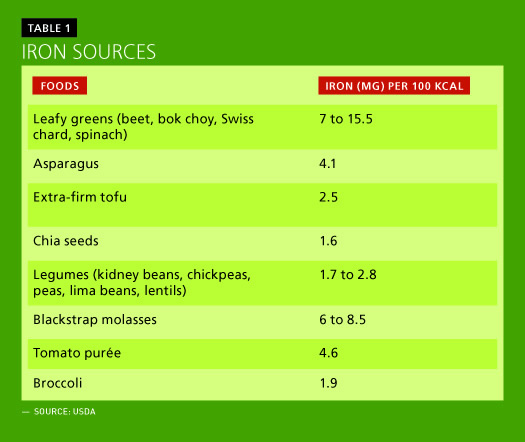

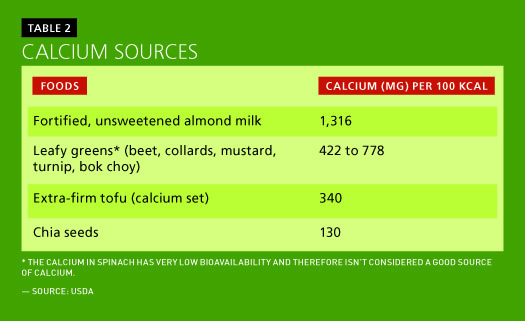

A vegan eating pattern uses a wider variety of foods to meet nutrient needs than the standard American diet. For example, rather than conceptualizing replacing the iron content in steak by a similar deck-of-cards-sized vegan meat, a vegan diet should contain smaller amounts of iron in a variety of foods eaten throughout the day. As a general rule, then, vegan clients should focus on this principle—eating smaller amounts of nutrients from nutrient-dense foods more often. Fruits, vegetables, legumes, and seeds can be extremely nutrient dense with a high concentration of nutrients per calorie, and many vegan clients may feel confident they easily can meet needs for nutrients of concern. Nonetheless, sources of common nutrients of concern and the importance of a diverse diet still should be emphasized. See Tables 1 and 2 on page 22 for nutrient density information for calcium and iron.

8. Focus More on Serving Sizes, Less on Calories

Whole plant foods contain insoluble and soluble fiber as well as resistant starch. All together, these components play useful roles in the vegan diet. They add volume to plants, which reduces caloric density. This allows clients to eat more (in volume) while eating less in calories. Dietitians don’t need to focus on counting calories from carbohydrates for vegan diets as they do traditionally for nonvegan diets, since a significant portion of calories from complex fiber-rich plant foods aren’t fully broken down and metabolized by the body during digestion; insoluble fiber doesn’t provide any energy to the body, while soluble fiber provides some through a breakdown into short-chain fatty acids.

Related to the previous point, standard serving sizes of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables are small. A serving size can equal one piece of fruit or 1/2 cup cooked vegetables. For a hungry vegan, it’s easy to eat three or four vegetable servings, a mere two cups, as part of a healthful bowl as described above. This is an important teaching point: The benefits of a plant-based diet largely come from what clients eat, not what they don’t eat. Larger servings of vegetables and fruits significantly raise nutrient and phytochemical consumption, a key part to successful vegan eating. One way to do this is to eat large salads. I recommend a minimum of 10 servings of fruits and vegetables per day for my clients.

Nuts, seeds, oil, avocado, and coconut are calorically dense plant foods unlike those mentioned above. Their density can help athletes, young children, and others meet caloric needs, but they shouldn’t be eaten with reckless abandon. Dietitians may be surprised to know that vegan versions of donuts, cheesesteaks, and ice cream are available in most major cities. Some vegans may subsist on these foods and will need to be steered toward eating whole plant foods.

9. Check for Other Food Restrictions

Food, no matter the client’s politics, is political, and many vegans are well aware of this. Concerns about working conditions, potentially harmful pesticides, and parent company issues, to name a few, also may influence food choices. Inquire about restrictions beyond the vegan diet and emphasize that overrestriction can lead to personal health issues. One way to address this while respecting clients’ choices is to stress that they need adequate health to continue doing the work they do. It’s possible to find nearly all foods problematic in some way, though we all need to eat.

10. Recommend a Vitamin B12 Supplement

Clients who don’t eat animal products must take a vitamin B12 supplement. Myths abound in the vegan world that B12 can be found in tempeh, spirulina, and fermented foods, but these are analogues and therefore aren’t adequate sources. Vitamin B12 supplements are readily available in pill or liquid form. The Dietary Reference Intake for adults is 2.4 mcg per day.7 An excellent review on vitamin B12 by Jack Norris, RD, is available at www.veganhealth.org/b12/rec.

Dietitians may not agree with the motivations or food choices of all their clients, but for RDs to be viewed as nutrition experts, we need to be familiar with the intricacies of plant-based and vegan eating. Those who practice these eating patterns often are motivated to eat healthful foods and have done more research than the average client. This uniqueness can be used for positive outcomes. RDs can reach this population by recognizing what’s driving them and guiding them toward proper nutrition practices.

— Matthew Ruscigno, MPH, RD, is chief nutrition officer at Nutrinic, a plant-based nutrition center, in Los Angeles. He thanks Eliza Mellion, MS, RD, for contributing her expertise to this article.

References

1. Wright N, Wilson L, Smith M, Duncan B, McHugh P. The BROAD study: a randomised controlled trial using a whole food plant-based diet in the community for obesity, ischaemic heart disease or diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 2017;7(3):e256.

2. Kahleova H, Levin S, Barnard N. Cardio-metabolic benefits of plant-based diets. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):E848.

3. McMacken M, Shah S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(5):342-354.

4. Turner-McGrievy G, Mandes T, Crimarco A. A plant-based diet for overweight and obesity prevention and treatment. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(5):369-374.

5. How many adults in the US are vegetarian and vegan? The Vegetarian Resource Group website. http://www.vrg.org/nutshell/Polls/2016_adults_veg.htm. Accessed August 2, 2017.

6. Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: vegetarian diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(12):1970-1980.

7. Norris J. Vitamin B12 recommendations. VeganHealth.org website. www.veganhealth.org/b12/rec. Accessed August 12, 2017.

[Sidebars]

VEGAN MEAL PLATES DESIGNED BY RDS

Several dietitians have designed their own visual MyPlate-style vegan meal planning diagrams. These visuals offer an easy-to-navigate guide to constructing a balanced plant-based meal.

• Brenda Davis, RD: The Vegan Plate (brendadavisrd.com)

• Julieanna Hever, MS, RD: Plant-Based Dietitian’s Plant Based Nutrition Plate (plantbaseddietitian.com/the-plant-based-food-guide-pyramid)

• Jeff Novick, MS, RD, LD, LN: The Healthy Eating Placemat (jeffnovick.com)

• Virginia Messina, MPH, RD: The Plant Plate (theveganrd.com/vegan-nutrition-101)

NUTRITION RESOURCES DEVELOPED BY RDS

• “Plant-Based Diets: A Physician’s Guide” by Julieanna Hever, MS, RD, CPT (thepermanentejournal.org/2016//6192-diet.html)

• Vegetarian Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (vegetariannutrition.net)

• Vegetarian Resource Group (vrg.org)

• VeganHealth.org by Jack Norris, RD (veganhealth.org)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS

• The Plant-Powered Diet: The Lifelong Eating Plan for Achieving Optimal Health, Beginning Today by Sharon Palmer, RD

• Vegan for Life: Everything You Need to Know to Be Healthy and Fit on a Plant-Based Diet by Virginia Messina, MPH, RD, and Jack Norris, RD

• Becoming Vegan: The Complete Reference to Plant-Based Nutrition by Brenda Davis, RD, and Vesanto Melina, MS, RD

• Nutrition Guide for Clinicians: Second Edition by Neal Barnard, MD, and colleagues

• Vegetarian Sports Nutrition: Food Choices and Eating Plans for Fitness and Performance by D. Enette Larson-Meyer, PhD, RD

MATT’S FAVORITE RESOURCES FOR NEW RECIPES

• Meatless Monday, Johns Hopkins University (meatlessmonday.com)

• Plant Based on a Budget (plantbasedonabudget.com)

• Oh She Glows (ohsheglows.com)

• Isa Chandra Moskowitz (isachandra.com)

— MR