Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18, No. 11, P. 48

Learn What They Are, the Cultural Differences That May Influence These Disparities, and the Role of RDs and Diabetes Educators.

Suggested CDR Learning Codes: 1040, 3020, 5190

Suggested CDR Performance Indicators: 1.1.3, 1.3.5, 1.3.9, 8.2.1

CPE Level: 2

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

The incidence of obesity-associated diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in the United States and worldwide.1 Over the past 20 years, the rate of obesity has skyrocketed, with more than one-third of US adults and roughly 17% of children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 currently obese.2 Paralleling this rise in obesity is a three-fold increase in newly diagnosed diabetes in adults aged 19 to 79 between 1980 and 2014, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3 Because of this phenomenon—the rise in prevalence of both diabetes and obesity—many experts refer to them as a single problem, “diabesity,” and to their simultaneous spike in prevalence as the “twin epidemics.”1

While many perspectives exist on the origin of the twin epidemics, ranging from evolutionary to biological, lifestyle choices—such as being physically active, maintaining a healthy body weight, and following a healthful, balanced diet—are known to play a key role in preventing type 2 diabetes, influencing risk as much as 80% to 90%.4

Lifestyle choices and risk factors that influence the diabesity epidemic are shaped by cultural preferences, knowledge, and beliefs, as well as socioeconomic status and access to health care. Diabetes is most common among less educated individuals and those below the federal poverty line.5 Many African Americans and Hispanics are of a lower socioeconomic status and less likely than whites to have health insurance and have higher rates of diabetes.5 It’s crucial that when working with these populations, RDs and other health care professionals target their interventions toward reducing or eliminating barriers to a healthful lifestyle through culturally competent client-centered care.

This continuing education course discusses disparities in diabetes. Although some disparities exist among all of the minority groups in the United States, this course describes the factors that continue to drive the twin epidemics among African Americans and Hispanics. It highlights the cultural differences that may influence these disparities and explains how RDs and diabetes educators can play a role in reducing the prevalence of the disease, its risk factors, and comorbidities among minority groups. In addition, it discusses ways RDs can, through culturally competent motivational interviewing (MI) techniques, help minority individuals make sustainable behavioral changes to reduce their diabetes and obesity risk or to better manage diabetes.

Obesity

Obesity, defined as having excessive body fat and a corresponding BMI ≥30 kg/m2, affects one-third of all US adults.2 Those with obesity have a 20 to 50 times greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes than normal-weight individuals.2,5

Obesity also contributes to the development of other leading causes of death in the United States such as heart disease, stroke, and certain types of cancer. It results in an additional $1,500 in medical costs per person per year than those of normal weight individuals.2

Diabetes

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, according to National Diabetes Statistics Report data from 2010.6 In 2012, 29.1 million Americans (9.3% of the population) had diabetes. The overwhelming majority of these cases (95.7%) were type 2 diabetes. Notably, however, of the 29.1 million people with diabetes, an estimated 8.1 million were undiagnosed, demonstrating an apparent lack of screening and other preventative measures among some populations.6

Uncontrolled diabetes leads to complications such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, heart attack, stroke, vision impairment, kidney disease, and amputations. In 2012, it cost the United States $245 billion.6

Health Disparities Defined

Over the past century, the United States has become increasingly diverse, owing to an influx of immigrants. Rates of preventable diseases such as diabetes and obesity remain higher among minorities (ie, African Americans and Hispanics) compared with nonminorities.5

According to the CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report, between 2007 and 2010, African American adults (both men and women) had the highest prevalence of obesity, followed by Mexican Americans, compared with non-Hispanic whites.7 Likewise, results from one 2013 study, which used data from the Women’s Health Initiative, showed that diabetes rates are more than twice as high in African Americans and 1.8 times higher in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites.4 Perhaps most concerning, diabetes-related mortality was 2.2 times higher in African Americans and 1.5 times higher in Hispanics than in whites in 2010.8,9

While these health disparities are eye opening, they can be improved with alterations to the health care system designed to cater to cultural differences and the needs of minorities. Among other factors, health disparities result from discrimination; cultural, language, and literacy barriers; and lack of access to health care among minority groups.7 Therefore, health care providers should aim their interventions at reducing these factors to prevent and treat diabetes in an increasingly diverse population.

Diabetes in African and Hispanic Americans

According to 2011 data from the National Health Interview Survey, 12.7% of people with diabetes over the age of 18 were non-Hispanic African Americans, and 12.1% were Hispanic.8,9 Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes also was slightly higher in African Americans (9.3%) compared with Hispanics (9.2%).8,9

The prevalence of diabetes-related complications is high for Hispanic Americans and African Americans.8,9 In 2008, approximately 369 African Americans and 238 Hispanics out of 100,000 people with diabetes received treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). In addition, of 1,000 Americans with diabetes, about five African Americans underwent a lower leg amputation in 2009. These rates are disproportionately higher than those of non-Hispanic whites. African Americans and Hispanic Americans started ESRD treatment 2.4 and 1.6 times more often, respectively, compared with non-Hispanic whites.8,9 Two times more African Americans underwent a lower limb amputation compared with whites in 2009. Notably, prevalence of retinopathy was lower in Hispanics compared with whites with diabetes in 2011 (16.3% vs 18.3%); however, it was 1.2 times higher in African Americans (20.7%) compared with whites.9

Some possible reasons for these disparities are economic constraints and differences in the quality and extent of health care provided. For example, African Americans aged 40 and older received 20% fewer retinal eye examinations in 2009 compared with whites, which could have influenced the higher rates of vision impairment.8,9 The quality of the care provided can be largely influenced by providers’ cultural competence; if health care providers recognize and address cultural characteristics and preferences of ethnic groups, they may be more likely to provide optimal quality care to these patients.

It’s anticipated that by 2050, people of minority groups will constitute more than 50% of the population.10 With this anticipated change in US demographics, the US food supply has diversified to provide foods fundamental to different cuisines on both a physiological and religious level—where certain foods have a sacred meaning in some groups.

Besides influencing specific food choices, culture may play a vital role in shaping health beliefs and attitudes, eating patterns, and behaviors. Jason Pelzel, in the article “Championing Cultural Competence,” states that demonstrating cultural competence isn’t “simply understanding the beliefs and behaviors of different groups” but involves an “ever-evolving process of examining one’s own attitudes and acquiring the values, knowledge, skills, and attributes that will allow an individual to interact with other cultures.”10 In other words, RDs shouldn’t approach cultural competency with the intention of becoming experts in the culture but rather to gain an understanding of the culture so they can serve clients better.

It’s necessary for health professionals to engage in this process of cultural competence for several reasons. First, practicing cultural competence promotes the development of respect and trust between clients and counselors and facilitates meaningful discussions about diet that are crucial to making diet modifications. Moreover, it helps RDs provide suggestions tailored to the individuals and thus useful to them. And it allows RDs to connect with patients and develop culturally appropriate educational and promotional materials and meal plans that address ethnic health disparities.

Campinha-Bacote Model of Cultural Competence

Pezel’s belief that RDs and other health professionals must engage in cultural exploration to improve efficacy of care, is echoed in the Campinha-Bacote model of cultural competence. Josepha Campinha-Bacote, PhD, RN, MA, PMHCNS-BC, CTN-A, COA, FAAN, defines her model of cultural competence as “a process of becoming culturally competent, not being culturally competent,”11 calling for health professionals to continually engage in cultural discussions and experiences to further their knowledge rather than settling on a set of known facts, because of the complex and dynamic nature of culture and its relationship to individuals.

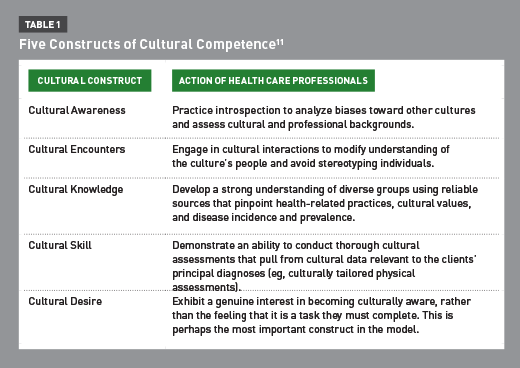

Within Campinha-Bacote’s model, she describes the five constructs of cultural competence, including cultural awareness, cultural encounters, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural desire.11 She defines “cultural awareness” as the “process of conducting a self-examination of one’s own biases toward other cultures and the in-depth exploration of one’s cultural and professional background.” Practitioners must practice self-awareness to reduce or eliminate any bias toward other groups and understand their own perspectives and places within the context of other cultures. During the process of self-examination, practitioners should question whether any of their health-related values, beliefs, and practices related to diabetes might influence the way they provide diabetes care and education. Similarly, Campinha-Bacote defines “cultural encounters” as the processes in which health care professionals engage in cultural interactions to modify their understanding of an individual’s culture and avoid stereotyping. This process requires practitioners to ask open-ended questions and listen attentively to the responses. For nutrition professionals, it’s an opportunity to explore cultural food influence.

“Cultural knowledge” is the process by which a health care professional procures—using reliable resources—a sound understanding of health-related practices, cultural values, and disease incidence and prevalence within a culture. For example, a practitioner may review research on the prevalence of diabetes within various cultures.

“Cultural skill” is defined as the ability of professionals to conduct a thorough cultural assessment. This assessment may include a culturally tailored physical assessment and must draw from cultural data relevant to the client’s principal diagnosis. Asking open-ended questions is essential to developing cultural skill.

Finally, “cultural desire” is the genuine interest among practitioners to become culturally aware, rather than the feeling that they “have to.” This may be the most important concept, because this internal willingness drives cultural competency and is crucial to providing sincere care to patients of differing ethnicities. However, it must not be understated that all of the five constructs are important to delivering care to minorities. These constructs are summarized in Table 1.11

Minority Populations

Developing cultural competence when working with minority populations involves understanding demographics and health beliefs as well as dietary choices, preferences, and patterns. Because African American and Hispanic American populations are vast, a discussion of their cultures may not be representative of all those within the group. However, this discussion can help elucidate commonly held group beliefs and practices, which in turn should help RDs understand the cultural factors contributing to the current health disparities in the United States and develop a cultural sensitivity to their clients and patients.

Who Are African Americans?

In a technical sense, African Americans are those who make up one of the major racial groups of the US census, “Black or African American.”12 The Office of Management and Budget defines the group as persons with origins in the Black racial groups of Africa, or who have identified on the census that they are African American, Black, Negro, Sub-Saharan African (eg, Kenyan and Nigerian), or Afro-Caribbean (eg, Haitian and Jamaican). These individuals also may identify as “Black or African American alone,” or as “Black or African American” in combination with another race, such as Asian, American Indian, Alaska native, white, or Hispanic.12

Demographics

African Americans and individuals who identify as African American in combination with another race constitute the second largest minority population of the United States.13 In 2013, about 45 million African Americans, including those of more than one race, were living in the United States—approximately 15.2% of the US population.7 In addition, those who identified as only African American represented 13.2% of the total US population (41.7 million people). The total number of African Americans is growing. Between 2000 and 2010, the “black alone” population and the “black alone or in combination” population grew by 12% and 15%, respectively. Based on these data, the total African American population is expected to climb to 74.5 million by 2060, according to projections by the US Census Bureau.7

African Americans are largely concentrated in the South, where they constitute the greatest proportion of the total population, and in pockets of metropolitan cities across the nation.7 In 2011, approximately 55% of all African Americans lived in southern regions of the United States.7 In 2013, nearly 60% of all people who identified as black lived in 10 states, including the following, from highest to lowest population: New York, Florida, Texas, Georgia, California, North Carolina, Illinois, Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio.12

Despite this increase in the African American population, blacks remain less educated, have lower incomes, and have less health insurance than whites.13 In 2012, fewer non-Hispanic blacks over the age of 25 earned at least a high school diploma compared with non-Hispanic whites (83% vs 92%).13 This discrepancy correlates with income gaps; in 2012, the average African American household earned $22,803 less than the average non-Hispanic white household ($33,762 vs $56,565, respectively). Moreover, in 2012, only 50.4% of African Americans had private health insurance, compared with 74.4% of non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, 40.6% of African Americans relied on Medicaid, compared with 29.3% of non-Hispanic whites.13 These disparities in income, education level, and health insurance use correlate with the present health disparities, as they affect and are affected by one’s health beliefs and level of medical care.

Health Beliefs

The traditional belief system for African Americans emphasizes the importance of maintaining a moderate lifestyle, which involves keeping one’s body clean and protected from natural elements (eg, the cold), and consuming a proper diet for maintaining one’s health and preventing changes in the blood.14 In effect, the culture traditionally classifies illness as either “natural” illness, which results from poor hygienic and/or nutritional practices and “unnatural” illness, which results from sources outside of one’s control. Many African Americans who adhere to the traditional belief system may believe that doctors are incapable of understanding or treating “unnatural” illnesses, and resort to traditional healers or healing methods rather than medications and science-based therapies.14 For those with hypertension and diabetes, folk ideas that involve the health of the blood can prove to be a great barrier to accepting needed treatment. Patients may not seek help from credible sources, or worse, may receive advice from sources that do more harm than good.

The Tuskegee experiment conducted between 1932 and 1972—in which African American men were unknowingly allowed to live with deadly syphilis infections and prevented from receiving penicillin in 1947 when it became widely available to cure the disease—also may explain mistrust of the health care system.

Communication gaps or trust barriers between health care professionals and patients could leave patients at a further disadvantage if professionals don’t practice cultural competency and sensitivity in their counseling.14 Nutrition professionals must assess a patient’s understanding of an illness and its cause and how he or she believes it’s properly treated.14

Food Choices, Taste, and Predilections

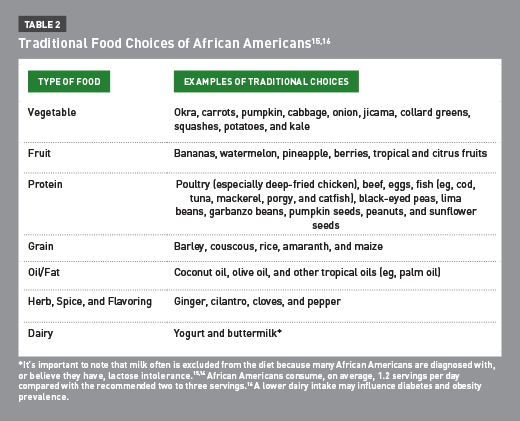

Having a basic understanding of traditional foods of African American heritage can help RDs develop a rapport with and tailor their nutrition interventions to their clients. It’s important to know the foods commonly eaten within the major food groups to aid in diet recall and nutrient analysis.15 Common heritage foods are listed in Table 2.15,16

RDs should be familiar with foods common to the culture. Food preferences, preparation, and meal patterns vary based on an individual’s traditional cuisines of the Caribbean, Africa, South America, or the American South. However, in general, African Americans prefer energy-dense foods.5 Based on their traditional food choices, their diets also may consist of a large variety of colorful vegetables (especially leafy greens), fish, and beans, which could be beneficial when making dietary adjustments. Changing cooking methods, such as frying to baking, can increase the nutritional value of foods.

Who Are Hispanic Americans?

The Office of Management and Budget defines Hispanics or Latinos as persons who have origins in Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, South America or Central America, or other Spanish cultures or origins, regardless of their race.7

Demographics

In the United States, the Hispanic population is the single largest minority population.7 In 2013, about 54 million Hispanics were living in the United States—approximately 17% of the US population.7 The Hispanic population has undergone rapid growth; between 2000 and 2010, it grew by 43%, which is more than any other minority group. The population is expected to number 128.8 million by 2060, according to projections by the US Census Bureau.7

In 2012, Mexicans made up the largest percentage of the Hispanic population (64%), followed by others (13.7%) and Puerto Ricans (9.4%).7

In 2010, more than one-half of the Hispanic population in the United States resided in only three states: California, Texas, and Florida. In 2013, Hispanics made up 47.3% of New York’s total population, the highest percentage among all states.California had the largest population of Hispanics compared with other states, totaling 14.7 million.7,17

Hispanics, like African Americans, are more likely to be less educated than non-Hispanic whites, and less likely to have health insurance than whites. In 2012, only 6.8% of college students were Hispanic, and only 70.1% of Hispanics had some form of health insurance.7

Health Beliefs

Family plays a crucial role in Hispanic culture, and its influence extends into the realm of health care. In regard to mental health, many Hispanics believe that most personal and interpersonal problems can be solved within the family unit and that only those who are severely emotionally disturbed should seek professional help.18 Similarly, intimate thoughts and concerns should be shared only with the immediate family, and men are expected not to complain or show weakness except among close friends. This inhibits meaningful communication between individuals of this group and their health care providers. To help close the communication gap and provide the best possible care, professionals must listen without judgment as patients describe health practices, rituals, or beliefs to better understand them and steer the patient away from any that might be harmful. Family is also largely involved in a patient’s health care decisions. Younger family members typically will pay more attention to their parents’ advice than to a doctor’s.18 Thus, professionals must involve the family in decision-making to make sustainable changes.

One advantage among Hispanics receiving health care is the respect they show to doctors. Hispanic patients prefer an “authoritarian-paternalistic type” relationship, in which they trust that their doctor will choose the best treatment for them. Still, some Mexican immigrants hold a fatalistic belief that one’s health is in God’s hands. Rather than seeking medical help, these individuals may seek treatment for illnesses from folk healers or herbal remedies, impeding their care.18 However, by practicing cultural competence and sensitivity, RDs can gradually move patients toward more scientific practices to help improve their patients’ obesity- and diabetes-related health outcomes.

Food Choices, Taste, and Predilections

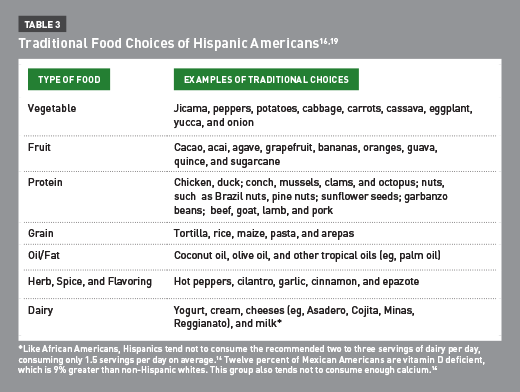

Research shows that acculturation—the process of moving away from one’s culture—largely influences diabetes risk for Hispanics.16 Studies demonstrate that high acculturation is associated with less healthful diets and a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes as well as increased rates of high blood pressure. As individuals become more acculturated, they tend to choose processed and fast foods rather than home-cooked meals made with wholesome ingredients. This leads to poorer diet quality and puts them at a greater risk of developing diabetes and other chronic diseases. In contrast, Hispanics who follow a more healthful traditional diet than the typical American diet have a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.16 This diet is summarized in Table 3.19

The medical professional must encourage Latino immigrants and those of Latino descent to maintain a traditional diet that includes whole grains (eg, corn), as well as an abundance of the aforementioned fruits, vegetables, and protein sources, such as beans, fish, and low-fat milk. Most important, RDs should encourage preparing meals at home and steer clients away from reliance on restaurant and ready-prepared foods that lead to poorer diet quality.

Nutrition Communication and Counseling Strategies

To effectively provide culturally competent care, RDs should use nutrition communication and counseling strategies. Among their skills should be the ability to ascertain each patient’s stage of change and empower the patient to make sustainable changes through means such as motivational interviewing and the American Association of Diabetes Educators’ Seven (AADE7) Diabetes Self-management Factors.

Stages of Change

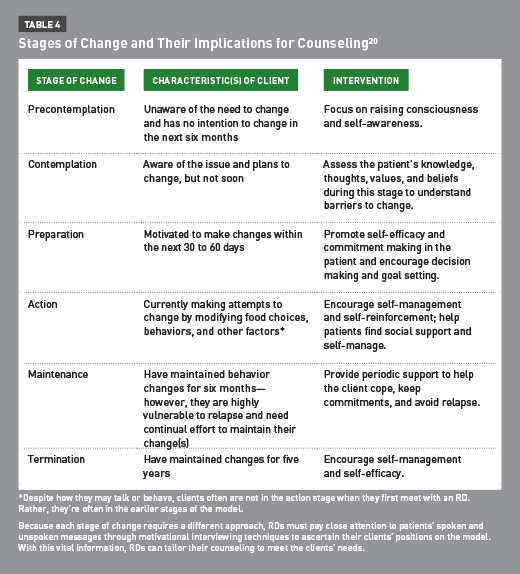

The Prochaska and colleagues’ Stages of Change Model is used to assess an individual’s awareness of the need to change and willingness to change.20 According to the developers, change is not a single event, but a process with five specific stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. These stages and their indications for counseling are summarized in Table 4, along with the ultimate goal, termination.20

It’s fundamentally important that RDs identify their clients’ stages of change so they can tailor their approaches to the particular stages. For example, if clients are in precontemplation, dietitians should ask more open-ended questions to enable clients to discuss and reflect on their health beliefs, lifestyles, and habits. This type of questioning leads to better self-awareness, enabling clients to recognize the need for change. If clients are in action, for example, they’re already making changes and recognize the importance of making those changes. At this stage, dietitians should ask more questions about progress and affirm the clients’ efforts to keep on track.

It’s important to note that most clients are in precontemplation or contemplation when they seek dietary counsel, even if they seem further along on the model.20 If RDs wrongly assume clients have reached a later threshold, they can overwhelm clients, which could result in clients not returning for care.20 If RDs know the stages, they can apply them in practice to ultimately help clients make sustainable behavior change.

Motivational Interviewing

RDs can’t simply make patients change by telling them what to do or why they should do it; these strategies usually have the opposite effect on clients. They must therefore empower clients to make changes and progress through the stages of change in an individualized manner.

In diabetes management, motivational interviewing has become the accepted model because it provides client-centered counseling aimed at making sustainable behavioral changes.21 According to this model, the patient and counselor make joint decisions that respect the patient’s individual needs and preferences. In this way, the counselor acts as a guide, honoring client autonomy rather than directing the patient’s actions.

The following four basic skills and techniques used by counselors in motivational interviewing can be summarized in the OARS acronym:

• open-ended questions;

• affirmations;

• reflective listening; and

• summaries.

Asking open-ended questions (eg, “What will you do first?) invites clients to elaborate and tell their stories in their own words rather than delivering “yes” or “no” responses. Using affirmations, or accentuating positive statements no matter how big or small (eg, “You are determined to go to the gym even though you had a busy day”) helps build rapport and can increase the client’s self-efficacy. Using reflective listening (eg, “What I hear you saying is that you want to lower your blood sugar”) allows clients to reflect on what they have said, which may help promote self-awareness. Finally, providing summaries, especially of “change talk,” helps ensure there’s clear communication and helps create forward momentum toward change (eg, “What I hear you saying is that you want to start checking your glucose levels.” In this statement, the RD reflects the client’s interest in making a change, expressed in the word “want”). With these techniques, the counselor can help the client discover and rectify ambivalence and overcome barriers to change by encouraging self-reflection and promoting self-efficacy. Ultimately, motivational interviewing helps patients achieve improved outcomes in care, especially for patients with diabetes.21

AADE7 Diabetes Self-Management Factors

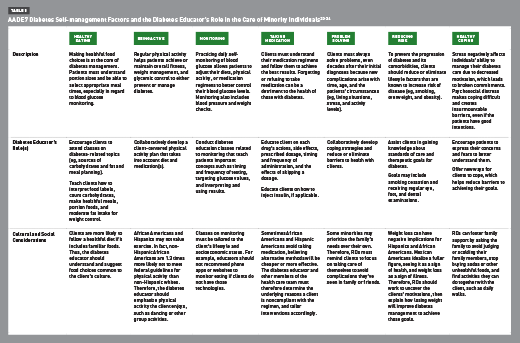

The AADE7 Diabetes Self-management Factors can be used in conjunction with motivational interviewing because they encourage patients to become knowledgeable about their care with the RD’s guidance. The AADE identifies seven self-care behaviors related to effective diabetes management: healthy eating, being active, monitoring, taking medication, problem solving, reducing risks, and healthy coping.22 These concepts and the cultural considerations of each minority group are described in Table 5.22-24

Although clients learn to manage their own care with the seven factors, RDs and diabetes educators should guide them by providing education and helping them set goals and cope.

Moving Forward

The twin epidemics of diabetes and obesity are growing in incidence and prevalence in the United States, especially among minority groups. African American and Hispanic populations have higher rates of obesity and diabetes compared with non-Hispanic whites, highlighting a major health disparity between ethnic groups. This disparity is caused by numerous factors, including educational and socioeconomic discrepancies and cultural barriers. It’s also greatly influenced by lifestyle, diet, and health beliefs, at which RDs and CDEs can target their interventions. Lifestyle and diet modifications such as maintaining or achieving a healthier weight can reduce diabetes risk by as much as 90%. Therefore, RDs should use client-centered, culturally competent counseling techniques and understand the tenets of motivational interviewing and the AADE7 Diabetes Self-management Factors to break barriers to change among minority groups.

— Annemarie Miller, RDN, is a retail dietitian for ShopRite supermarkets in the North Eastern United States, where she provides one-on-one nutrition counseling and group classes to shoppers and members of the community.

— Constance Brown-Riggs, MSEd, RD, CDE, CDN, is past national spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, specializing in African American nutrition, and author of The African American Guide to Living Well With Diabetes and Eating Soulfully and Healthfully With Diabetes.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals should be better able to:

1. Compare the prevalence rates of obesity and diabetes for African Americans and Hispanic Americans with nonminorities.

2. Distinguish key cultural characteristics, such as demographics, health beliefs, and traditional food choices of the two minority groups.

3. Describe how cultural barriers between the counselor and client can inhibit care.

4. Practice cultural competence according to the Campinha-Bacote model.

5. Apply the tenets of motivational interviewing, stages of change, and the American Association of Diabetes’ Educators Seven Diabetes Self-management Factors with cultural considerations when counseling clients with diabetes.

CPE Monthly Examination

1. According to the most recent data from the National Health Interview Survey, what is the order of diabetes prevalence among the following ethnic groups, from highest to lowest prevalence?

a. Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites

b. Non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic whites

c. Non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics or Latinos

d. Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks

2. According to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, what is the order of obesity prevalence among the following ethnic groups, from highest to lowest prevalence?

a. Non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic whites

b. Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites

c. Non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics or Latinos

d. Hispanics or Latinos, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks

3. How much greater is the risk of diabetes in obese individuals compared with normal-weight individuals?

a. 1.5 times

b. 2 to 4 times

c. 5 times

d. 20 to 50 times

4. African Americans of a lower socioeconomic status are most likely to do which of the following?

a. Take a health professional’s advice to manage their disease or illness

b. Seek culturally traditional healing methods for their disease or illness

c. Deny the existence of their disease or illness

d. Take advantage of all the options available in their insurance plan

5. Which of the following food groups is lacking in the African American and Hispanic American’s traditional diets?

a. Protein

b. Dairy

c. Grains

d. Fruits

6. During an initial counseling session, in which stage of change is a new client most likely to be?

a. Contemplation

b. Action

c. Maintenance

d. Termination

7. Why is the ability to practice cultural competence important in the dietetics field?

a. The federal government mandates that RDs deliver care that caters to cultural preferences.

b. The RD will become expert in the culture and will know everything he or she needs to help clients.

c. Clients will refer their friends to the RD, which will help to expand the field.

d. The RD will grow to understand clients and their cultures better and will help clients make practical changes.

8. After speaking with an RD, a new Hispanic client says, “I don’t think there’s anything I can do to become healthier; God will take care of me.” What cultural norm is he displaying and in what stage of change is he?

a. Resistance of treatment and precontemplation

b. Fatalism and precontemplation

c. Cultural bias and contemplation

d. Faith and preparation

9. On whose opinions do minorities tend to rely when making decisions?

a. The media

b. Their peers

c. Their families

d. Their health care team

10. Which of the following behaviors or attitudes is least likely to be a barrier to healthful living among African American and Hispanic American individuals?

a. Idealizing a fuller figure

b. Seeking alternative medicines for diabetes

c. Preferring dancing, sports, or group activities over activities typically deemed exercise

d. Following nutrition and health advice from sources that are not credentialed (eg, family and friends)

References

1. Farag YM, Gaballa MR. Diabesity: an overview of a rising epidemic. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(1):28-35.

2. Adult obesity facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. Updated September 9, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2015.

3. Annual number (in thousands) of new cases of diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 18-79 years, United States, 1980-2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig1.htm. Updated December 1, 2015. Accessed May 19, 2016.

4. Ma Y, Hébert JR, Balasubramanian R, et al. All-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality rates in postmenopausal white, black, Hispanic, and Asian Women with and without diabetes in the United States: the Women’s Health Initiative, 1993-2009. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(10):1533-1541.

5. Katzmarzyk PT, Staiano AE. New race and ethnicity standards: elucidating health disparities in diabetes. BMC Med. 2012;10:42.

6. Statistics about diabetes. American Diabetes Association website. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Updated February 19, 2015. Accessed May 5, 2015.

7. CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report (CHDIR). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/CHDIReport.html. Updated September 10, 2015.

8. Diabetes and African Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health website. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlID=18. Updated November 5, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2015.

9. Diabetes and Hispanic Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health website. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlID=63. Updated June 13, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2015.

10. Pelzel J. Championing cultural competence. International Food Information Council Foundation website. http://www.foodinsight.org/Championing_Cultural_Competence. Updated October 20, 2014. Accessed May 7, 2015.

11. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services. Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates website. http://transculturalcare.net/the-process-of-cultural-competence-in-the-delivery-of-healthcare-services/. Updated 2015. Accessed May 7, 2015.

12. The Black population: 2010. US Census Bureau website. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-06.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed May 7, 2015.

13. Profile: Black/African Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health website. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=61. Updated June 2014. Accessed May 7, 2015.

14. Snow LF. Traditional health beliefs and practices among lower class black Americans. West J Med. 1983;139(6):820-828.

15. African heritage foods. Oldways website. http://oldwayspt.org/resources/heritage-pyramids/african-diet-pyramid/african-heritage-foods. Accessed May 7, 2015.

16. Bailey RK, Fileti CP, Keith J, Tropez-Sims S, Price W, Allison-Ottey SD. Lactose intolerance and health disparities among African Americans and Hispanic Americans: an updated consensus statement. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105(2):112-127.

17. The Hispanic population: 2010. US Census Bureau website. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Published May 2011. Accessed May 8, 2015.

18. Poma PA. Hispanic cultural influences on medical practice. J Natl Med Assoc. 1983;75(10):941-946.

19. Latin American diet foods. Oldways website. http://oldwayspt.org/resources/heritage-pyramids/latino-diet-pyramid/latino-diet-foods. Accessed May 9, 2015.

20. Holli BB, Beto JA. Stages and processes of health behavior change. In: Troy DB, ed. Nutrition Counseling and Education Skills for Dietetics Professionals. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:107-133.

21. Holli BB, Beto JA. Person-centered counseling. In: Troy DB, ed. Nutrition Counseling and Education Skills for Dietetics Professionals. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:79-105.

22. AADE7 self-care behaviors. American Association of Diabetes Educators website. http://www.diabeteseducator.org/ProfessionalResources/AADE7/. Accessed May 10, 2015.

23. Living with diabetes. American Association of Diabetes Educators website. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/patient-resources/awareness-campaign-materials/patient_brochure_final.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed April 7, 2016.

24. Obesity and African Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health website. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=25. Updated October 15, 2013. Accessed May 13, 2015.