June/July 2024 Issue

June/July 2024 Issue

Diagnosing Malnutrition: AAIM or GLIM?

By Jennifer Doley, MBA, RD, CNSC, FAND

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 26 No. 6 P. 22

Learn the ins and outs of these two sets of criteria.

Malnutrition has garnered increased focus in the health care community in recent decades. It’s linked to poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, including increased mortality, longer length of hospital and ICU stay, higher costs of care and readmission rates, impaired wound healing, and increased incidence of infections and pressure injuries. Identification of malnutrition is important so that nutritional interventions can be implemented to reduce the risk and incidence of poor outcomes.1

Like any medical condition, a consensus among health care professionals regarding malnutrition diagnostic parameters is needed. Many diagnostic criteria for malnutrition have been proposed, including the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA),2 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Indicators for Malnutrition (AAIM),1 and Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM).3 The SGA, published in 1982, has been validated in a number of settings and is often used as the standard in validation studies of other sets of criteria like AAIM and GLIM. SGA criteria categories include weight and intake changes, gastrointestinal symptoms, functional capacity, disease burden, and physical findings (muscle loss, fat wasting, and fluid accumulation).2

Adoption of the GLIM criteria in the United States has been limited; however, it has been more widely adopted worldwide. A recent study of US-based hospitals showed a majority of respondents (89%) use the AAIM model to diagnose malnutrition.4

This article will focus on AAIM and GLIM, as they’re two of the most recently developed sets of criteria, in 2012 and 2019, respectively. It will describe AAIM and GLIM criteria, compare and contrast key similarities and differences, controversies surrounding these criteria, and how their use will impact the work of RDs in daily practice.

AAIM

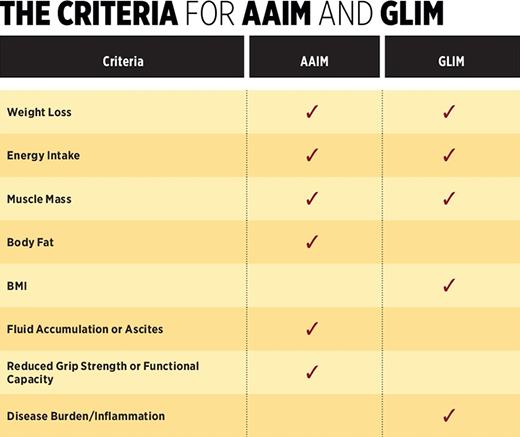

Developed collaboratively by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, the AAIM criteria for adults was published in 2012.1 AAIM is composed of six malnutrition indicators: unintentional weight loss, reduced intake, muscle wasting, fat loss, reduced hand grip strength, and fluid accumulation. Specific parameters are set for each indicator to diagnose either nonsevere (mild/moderate) or severe malnutrition.

To diagnose malnutrition, at least two of the six criteria should be present. Different criteria may fall into different severity categories—eg, weight loss for acute malnutrition is 1% to 2% in one week (moderate) and intake is ≤ 50% for five or more days (severe). Although the AAIM consensus statement doesn’t clarify how to assign a severity level in this case, it’s generally recommended that at least two criteria fall in the severe category in order to diagnose severe malnutrition.

GLIM

The GLIM criteria were developed by a coalition of several international professional nutrition societies, including the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, the Federacion Latinoamericana de Terapia Nutricional, Nutricion Clinica y Metabolism, and the Parenteral and Enteral Society of Asia, with the intent to reach a consensus on malnutrition criteria that could be applied globally.3 GLIM includes three phenotypic criteria: unintentional weight loss, reduced muscle mass, and low BMI; and two etiologic criteria: reduced food intake or assimilation and disease burden/inflammation.

In order to diagnose malnutrition, at least one criterion from each category should be present. To determine severity, only the phenotypic criteria are used. Like AAIM, GLIM recognizes only two severity categories (mild/moderate and severe), each of which has specific thresholds. However, GLIM specifies that only one phenotypic criterion in the severe category is needed to diagnose severe malnutrition—eg, weight loss of 5% to 10% in the last six months (moderate) and

BMI < 20 for individuals ≥ 70 years of age (severe).

Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam

While AAIM and GLIM don’t share all of the same criteria, they do have important similarities. One key characteristic of both modalities is the inclusion of criteria that can only be fully identified by a physical exam. While weight loss, inadequate intake, and disease processes can be identified by review of a medical record and verbal communication with a patient or caregiver, accurately identifying criteria such as muscle wasting, fat loss, and fluid accumulation requires a hands-on approach.

The publication of the SGA criteria for malnutrition in 1982 introduced the concept of a physical exam to assess for malnutrition, as the SGA criteria include muscle and fat loss, functional capacity, and fluid accumulation.2 Although the SGA has been validated in a number of settings in patients with different diseases, it’s unclear how widely it has been adopted internationally. The use of a physical exam to identify malnutrition didn’t become a more common practice for RDs until the AAIM criteria were published in 2012.

Now known as a Nutrition Focused Physical Exam, it’s considered a necessary practice standard in the assessment of nutritional status, and in 2017 was added as a core competency in dietetics education5 and a standard of practice for RDs.6

Etiology-Based Diagnostic Construct

Another key similarity of AAIM and GLIM is that they use an etiology-based framework. As with any medical condition, it’s important to identify the cause (etiology) of malnutrition in order to develop an effective treatment plan. The AAIM etiologic groups are acute illness, chronic illness, and social/environmental circumstances.1 The GLIM etiologic criteria are reduced food intake or assimilation and inflammation (disease).3 Although these etiological categories don’t share the same terminology, the construct is essentially the same: illness- and nonillness-related.

Illness-Related Malnutrition

In the AAIM construct, illness-related etiologies—acute and chronic—are distinguished by the degree of inflammation and duration of the symptoms. Acute illness-related malnutrition is characterized by conditions that result in severe inflammation such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, severe sepsis, trauma, or burns. Symptoms are considered acute if they’re present for less than three months. Chronic illness-related malnutrition is characterized by lower level chronic continuous or intermittent inflammation, which can be caused by a number of different diseases or conditions. Symptoms are considered chronic if they’re present for greater than three months.1

GLIM doesn’t distinguish between acute and chronic illness.3 However, although inflammation itself isn’t considered a diagnostic criterion for AAIM, the workgroup found value in using acute or chronic inflammation to help categorize malnutrition as acute or chronic illness-related1 Response to malnutrition treatments is limited in patients with severe inflammation; therefore, it’s important to consider the presence and degree of inflammation when implementing and monitoring the efficacy of a malnutrition treatment plan.

Social/Environmental/Reduced Intake-Related Malnutrition

AAIM’s social or environmental circumstances category and GLIM’s reduced intake or assimilation category are considered solely a starvation state that’s not associated with inflammation.1,3 Causes may be related to a noninflammatory condition that results in inadequate food intake, such as anorexia nervosa or reduced absorption as seen in short bowel syndrome. More frequently, however, causes are related to social determinants of health that impair an individual’s ability to obtain food, such as financial limitations, transportation issues, or limited availability of food within a specific geographic location. Limited access to utilities such as clean water and electricity, as well as impaired functional status and lack of social support can also limit a person’s ability to store and prepare food.

Overlapping Etiologies

Using an etiology-based framework to diagnose malnutrition helps RDs treat the patient with effective interventions. An RD would implement many different interventions for a patient with acute illness-related malnutrition than they would for one with social circumstances resulting in reduced food intake. However, one challenge in diagnosing malnutrition using the etiology-based approach is identifying all etiologies, as more than one may be present. A patient with chronic disease-related malnutrition may have an acute event or a flare-up of their chronic illness that worsens their malnutrition, and they then might meet the criteria for both acute and chronic illness-related malnutrition under the AAIM construct.

The RD uses all the available evidence and their clinical skills and judgment to diagnose malnutrition and identify the etiology or etiologies. Although the AAIM consensus statement doesn’t make specific recommendations on documenting more than one etiology,1 specific approaches might include documentation of “acute on chronic” malnutrition, “chronic malnutrition exacerbated by acute illness,” or writing two separate diagnostic statements. All relevant findings should be documented whether they fit into the chronic or acute categories or both.

Nutrition goals for an acute condition should take priority until it has resolved, then goals can be adjusted to address the chronic issue. For example, in a patient with chronic malnutrition related to chronic pulmonary disease, the goal may be to increase food intake to provide sufficient calories and protein for repletion. However, if the patient develops acute respiratory failure, providing that same number of calories and protein may no longer be appropriate, considering metabolic abnormalities that occur in critical illness. After the acute respiratory failure has resolved, meeting nutritional needs to treat chronic malnutrition would be an appropriate goal again. For this reason, identifying etiologies and prioritizing treatment goals is critically important.

Ultimately, documenting “correctly” with specific terminology isn’t the primary concern or focus. Most important is helping the patient by determining potential etiologies in order to develop and prioritize appropriate goals and interventions.

Criteria

As noted, AAIM and GLIM share some criteria, but there are notable differences. Here are a few.

Muscle Loss

GLIM specifically states the presence and severity level of muscle loss should be determined by “validated assessment methods”; however, it didn’t come to a consensus on the best methods to assess muscle loss.3 Furthermore, a clarifying document was released in 2022 that provides additional guidance.7 Body composition measurements such as bioelectrical impedance, dual X-ray absorptiometry, CT, and ultrasound are validated and most accurate, and thus are the preferred tools for assessing muscle mass.

That being said, there are limitations to each, as these methods are often not readily available to most clinicians outside of a research setting. The GLIM working group recommended the use of anthropometry and physical exam when technological approaches aren’t feasible. Calf circumference and mid-arm muscle circumference are easily obtained measurements that can be compared with established standards to provide an objective measure of muscle mass. While a physical exam is more subjective, it’s been validated as a technique to identify muscle wasting when it’s performed by a trained RD.7

Inflammation

Under the AAIM construct, inflammation is used to help identify whether disease-

related malnutrition is chronic or acute; however, it is itself not a criterion.1 Inflammation is an etiologic criterion for GLIM, but the original GLIM guidelines didn’t provide much guidance on how to identify inflammation.3

In January, guidelines were released for identifying inflammation in relation to the GLIM criteria.8 Research is limited, so the guidelines are based on expert opinion. One key takeaway is that the presence of a disease or condition that’s usually associated with inflammation is sufficient to meet the inflammation criterion under the GLIM diagnostic model. A lab result may support the identification of inflammation; however, it’s not required. If lab results are used, the GLIM workgroup recommends C-reactive protein, a positive acute-phase protein that becomes elevated in the presence of inflammation. Unlike AAIM, the GLIM diagnostic model doesn’t distinguish between acute and chronic disease-related malnutrition, therefore the presence of either acute severe inflammatory conditions or low-grade chronic inflammatory conditions are sufficient to meet the criterion.

BMI

Another difference between these diagnostic models is the inclusion of BMI in the GLIM criteria.3 There has been some controversy surrounding this criterion because of the known limitations in the use of BMI as a nutrition assessment tool. However, the GLIM group included BMI because GLIM is meant to be used globally, and BMI is more commonly used worldwide than it is in North America. BMI cutoffs for GLIM have been set for individuals based on age (greater than 70 years), as older individuals have the best health outcomes and morbidity at a higher BMI than is recommended for younger individuals. The GLIM group also set lower BMI cutoffs for Asian populations, but acknowledge additional research is needed to back this recommendation.3

The less frequent use of BMI in North America in malnutrition assessment is due to the region’s higher incidence of overweight and obesity. An overweight or obese patient would need to lose a significant amount of weight to meet the BMI criterion, long after malnutrition initially occurred. However, BMI does have value in normal weight or underweight patients. Some underweight, chronically malnourished patients may not meet weight loss criteria, simply because they have no more weight to lose. In these cases, BMI is a useful criterion. It’s helpful as an indicator of total body weight state, much like percent of “ideal” weight, but isn’t useful in assessing muscle mass because it doesn’t account for body composition.

Choosing AAIM or GLIM

So, which set of criteria should you choose? Both AAIM and GLIM have been validated in a number of settings, including hospitals, and additional validation research is ongoing.9,10 After the introduction of GLIM, the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition released a clarifying document stating that GLIM is “fully congruent” with approaches like AAIM and SGA.11 Whatever criteria are used, patient care should always be the focus. All available data—including Nutrition Focused Physical Exam findings—should be applied consistently, and potential etiologies identified to ensure the patient receives appropriate interventions to treat their malnutrition.

— Jennifer Doley, MBA, RD, CNSC, FAND, is a corporate malnutrition program manager with Morrison Healthcare. Previous roles include nutrition support specialist, clinical nutrition manager, regional clinical nutrition manager, and dietetic internship director.

References

1. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

2. Detsky A, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, et al. What is the subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987;11(1):8-13.

3. Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Correia ITD, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43(1):32-40.

4. Guenter P, Blackmer A, Malone A, et al. Current nutrition assessment practice: a 2022 survey. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023;38:998-1008.

5. Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics. ACEND Accreditation Standards for Nutrition and Dietetics Internship Programs (DI). Effective June 2017 to June 2022.

6. Andersen D, Baird S, Bates T, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Revised 2017 standards of practice in nutrition care and standards of professional performance for registered dietitian nutritionists. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(1):132-140.

7. Barazzoni R, Jensen GL, Correia MITD, et al. Guidance for assessment of the muscle mass phenotypic criterion for the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) diagnosis of malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2022;41:1425-1433.

8. Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Ballesteros-Pomar MD, et al. Guidance for assessment of the inflammation etiologic criterion for the GLIM diagnosis of malnutrition: a modified Delphi approach. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2024;48(2):145-154.

9. Compher C, Jensen GL, Malone A, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with malnutrition diagnosed by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Indicators of Malnutrition: a systematic review of content validity and meta-analysis of predictive validity [published online February 6, 2024]. J Acad Nutr Diet. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2024.02.002.

10. Correia MITD, Tappenden KA, Malone A, et al. Utilization and validation of the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM): a scoping review. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(3):687-697.

11. Global leadership initiative on malnutrition statement. American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition website. https://www.eatrightpro.org/practice/dietetics-resources/clinical-malnutrition/global-leadership-initiative-on-malnutrition-statement. Accessed April 17, 2024.