Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18, No. 10, P. 36

Nutrition for Both Ends of the Life Cycle

Every day, approximately 3.3 million children and 120,00 adults consume meals and snacks funded by the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), a federal nutrition assistance program administered by the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service. CACFP has the broadest scope of any of the 15 USDA food programs, serving individuals across the lifespan: infants, young children, and seniors in day care programs; at-risk school-age youth enrolled in after-school programs; and residents of emergency shelters.

Similar to the National School Lunch Program, CACFP works with state agencies to reimburse facilities for meals that adhere to its nutrition guidelines. Newly revamped under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA), CACFP meals were brought in line with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and now contain more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Like other food programs, CACFP targets low-income individuals and helps to fill nutritional gaps that stem from food insecurity, which affects CACFP’s target populations, as explained by Monsivais and colleagues in the May 2011 issue of the Journal of the American Dietetic Association. According to “Household Food Security in the United States,” a 2009 USDA Economic Research Service report by Nord and colleagues, 23% of all American households with children younger than 6 reported not having enough food at a given time. Food insecurity is particularly dangerous for children because it can hinder growth, development, and learning. Food-insecure children are at risk of suboptimal intakes of key nutrients such as folate, vitamin C, and fiber, according to Casey and colleagues in the April 2001 issue of Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. Food insecurity also is associated with problems in neurocognitive development, learning, and socioemotional development, according to Cook and Frank in a June 2008 issue of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Seniors also are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of food-insecure seniors in America doubled to 8.4%, according to Feeding America, an antihunger advocacy group. The group reported in Spotlight on Senior Health: Adverse Health Outcomes of Food Insecure Older Americans that food-insecure seniors consumed fewer calories and lower levels of vital nutrients such as iron and protein. In addition, the report showed that these individuals are 53% more likely to report a heart attack, 52% more likely to develop asthma, and 40% more likely to report congestive heart failure, as well as to experience limitations in activities of daily living such as dressing, eating, and bathing.

Paradoxically, overweight and obesity can coexist with food insecurity. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2011, low-income preschoolers possess considerable risks of overweight and obesity, with rates nearing 30%. Poverty remains the most likely determinant of both food insecurity and obesity. The stress that food insecurity can cause is thought to contribute to obesity, according to a study presented by Fiese and colleagues at the biennial meeting for the Society for Research in Child Development in April 2011.

Who Can Participate in CACFP?

The largest group served by CACFP (93%) are children enrolled in day care. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, with 64.2% of mothers with children younger than 6 in the work force, childcare has become a “home away from home” for more than three-quarters of American children aged 3 to 5. Today, many children spend 28 to 40 hours per week in childcare, where they consume one-third to two-thirds of their daily calories and nutrition. Fiese and colleagues explain that for such children, preschool meals can represent the greater part of their weekday nourishment.

According to the USDA, around $3 billion in CACFP funds go to childcare meals, with two-thirds of this amount paid to large, center-based childcare facilities and one-third to smaller day care homes. Center-based childcare includes independent public or private day care centers, including Head Start preschools, which are required by law to participate in CACFP. A center-based preschool can report directly to the state agency that administers CACFP at the state level, normally the department of education or of health and human services. Centers also may choose a sponsoring organization to assist them, but the sponsor must be a state-approved organization or company. Sponsors can be nonprofit or community organizations, housing projects, or companies. Sponsors help a center maintain food and safety standards, complete eligibility and reimbursement paperwork, and provide CACFP training to center staff.

A center-based preschool has, on average, 60 to 70 children enrolled, with 53 to 57 in attendance daily. For-profit preschools with at least 25% of enrolled students documented as low income can participate. Center-based preschool students whose families have an annual income at or below 185% of the federal poverty level qualify for reduced-price meals, and those at 130% or below qualify for free meals.

Day care homes, which are small, often family-based operations with an average of seven children attending daily, must operate under a sponsor. Again, a sponsor can be an approved organization. CACFP uses a controversial two-tiered system designed to provide higher reimbursements to providers in lower-income areas. Tier I day care homes, which receive reimbursement rates roughly double the amount of Tier II centers, are those located in areas determined to be low income or that are based out of a home with an income below 185% of the federal poverty income guidelines. Tier II homes, which receive lower reimbursements, are those that don’t meet the location-income or the provider-income criteria. Some Tier II homes may qualify for Tier I reimbursements for the number of students whom they can identify as very low income.

Some food assistance advocates, including the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) based in Washington, D.C., criticize the two-tier system. In “Child and Adult Care Food Program: Participation Trends 2012,” a FRAC report, authors Cooper and Henchy state that since this system began in 1997, the overall number of childcare providers receiving CACFP has grown, but the number of childcare homes has dropped 30%. The requirements for small day care centers and day care homes can be expensive and challenging. Although homes can keep their tier status for five years, they must report enrollees’ eligibility for free or reduced-price meals on a monthly basis.

Adult day care facilities that provide structured, comprehensive nonresidential services to adults aged 60 and older and younger people who are functionally impaired may receive CACFP funding. For-profit adult centers may receive funds if at least 25% of their participants receive Social Security or Medicaid benefits. Meals are reimbursed in the same way as those for children, based on eligibility for reduced-price, free, or paid meals.

CACFP also provides supper and snack funding to after-school programs serving low-income and at-risk youth aged 18 and under. Eligible programs must be located in areas where at least 50% of participants are eligible for free and reduced-price meals based on school data. In addition, licensed and unlicensed emergency shelters serving homeless children, run by public or private organizations, were permitted to receive CACFP funding beginning in July 1999. Shelters may receive funding to serve up to three meals per day to homeless child residents.

New CACFP Food Standards

Based on longitudinal and cross-sectional data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort, which involved more than 4,000 participants, CACFP’s efforts have helped to improve the nutrient intake of its participants. Compared with low-income children of the same age enrolled in other types of nonparental care, children in Head Start (which funds its meals through CACFP) are reported to eat fruits, vegetables, and dairy foods on more occasions per week, and are less likely to be overweight or obese, another major concern for this population. These data were included in a report by Korenman in Early Childhood Quarterly, 2nd quarter 2013.

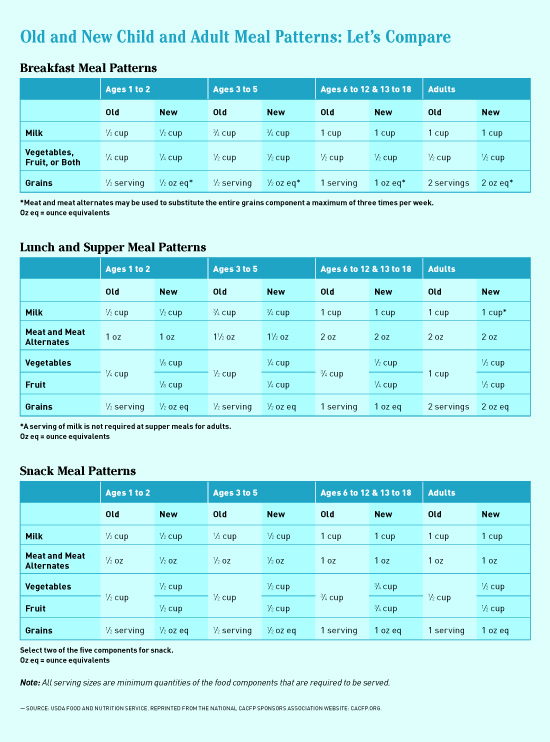

CACFP underwent its first major revisions to meal quality and meal patterns in 40 years when President Obama signed into law the HHFKA. The Institute of Medicine (IOM), the same body that sets federal guidelines for micronutrient intakes, provided the latest nutrition science and authoritative scientific recommendations to improve CACFP. The final rule was published in April 2016, with training and implementation slated for completion by October 2017. HHFKA called for the following changes to meal patterns and meal standards.

Fruits and Vegetables

Whereas CACFP’s previous meal pattern placed fruits and vegetables into one category, the new regulations split them into separate categories to increase the importance of each as distinct meal components, each of high value. In addition, preschools now can serve two vegetables at lunch and at dinner. The new regulations also specify that fruit juice served must be 100% juice and limited to one serving per day.

Whole Grains

Previous regulations didn’t address whole grains at all. But the new regulations specify that at least one daily serving of grains must be whole grain-rich, defined as grains containing 50% whole grain with the remainder being enriched grain or else 100% whole grain. The recommended best practice is to offer two servings per day. Grain-based desserts no longer can be counted towards the grain component of meals. In addition, beginning October 1, 2019, servings of grain foods will be measured in ounce equivalents rather than in cups to allow for more precision in meal planning.

Protein

The new regulations allow meat and meat alternates to be served in place of the grain component at breakfast up to three times per week. In addition, tofu is now acceptable as a meat alternative up to three times per week. This change was intended for cutting some of the carbohydrates that were formerly the go-to component of breakfast meals.

Added Sugar

To reduce the amount of added sugar in meals, the new regulations allow yogurt with no more than 23 g sugar per 6-oz serving. They also specify that breakfast cereals must contain no more than 6 g sugar per dry oz.

Milk

Only unflavored low-fat or fat-free milk must be served to children aged 2 and older. Nondairy substitutes may be served in place of milk to children with documented special dietary or medical needs.

Cooking Method

Frying is no longer allowed as an onsite cooking method.

Other Provisions

Food can’t be used as either reward or punishment. Children will eat meals family style, which means serving themselves from larger bowls of food shared with their peers. When teachers help children to serve themselves, they must offer the foods before serving them. The intent of these measures is to allow children to control which foods and how much food they’d like to eat.

CACFP Opportunities for RDs

CACFP’s 2011 report “Aligning Dietary Guidance for All” states several recommendations for future research. The first of these calls for finding ways that CACFP can “fill important gaps in knowledge of the role of CACFP in meeting the nutritional needs of program participants,” including finding out “how meal-time environmental factors can be used in CACFP childcare settings to help facilitate healthy eating” as well as “the best ways to educate and engage staff, parents, guardians, and caregivers.” Thus, there are opportunities for RDs to research ways to improve the program, especially the impacts and implementation of new food regulations.

CACFP allows discretion in menu planning so facilities can serve foods that suit local needs, preferences, and availability. Technical training, developed by the Institute for Child Nutrition (formerly the National Food Service Management Institute) for the USDA, provides training materials to states that then train sponsors or facilities. State agencies monitor sponsors at least three times per year, reviewing record keeping, meal counts, menus, licensing, and approval, and sometimes production records, meal observation, and administrative costs, according to Murphy and colleagues. There also are opportunities for RDs to assist in the administration, review, and management of CACFP at the national, state, and local levels.

Vicki Lipscomb, founder and president of Child Nutrition Program, Inc, in Charlotte, North Carolina, and current president of the National CACFP Sponsors Association, sees growing opportunities for RDs in CACFP sponsorship, regulation, and technical training of preschool staff and foodservice, and helping preschools to maximize their food dollars to bring kids the most nutritious foods possible. Although the new regulations were designed to be cost neutral, the addition of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is likely to raise costs for some facilities. For example, the IOM’s 2011 report predicted that the costs of implementing changes to CACFP would require reimbursements for home childcare providers to be raised by 31% to 44%.

Lipscomb believes that RDs working in a role like hers, at the helm of a sponsorship company or in a training role at the state agency or sponsor level, represents a growing need in the market. CACFP is expanding, she explains, especially in the number of eligible adult day care facilities and at-risk after school programs. Since facilities can use up to 15% of their meal reimbursement funds for administrative costs, there are business opportunities for capable sponsors. Lipscomb believes RDs are uniquely qualified to understand the food business and the nutrition sides of CACFP administration.

In addition, state agencies or sponsoring organizations provide nutrition education to childcare providers, children, and parents. The specific educational programs, or curricula, vary from state to state. In some states, RDs administer and manage them. Michelle Jackson, RDN, of Mamaroneck, New York, works with Head Start programs to assess BMIs of students, and counsels at-risk students and parents on how to prevent and manage overweight. Her work also involves ensuring that Head Start menus comply with CACFP guidelines, kitchen sanitation procedures are followed, and that children are eating family style with their teachers in their classrooms. The challenges she experiences are helping schools with accessing healthful food in the inner city and “helping parents of diverse backgrounds to understand the importance of a healthy weight during childhood.”

Jackson is encouraged by the cooks she has encountered, who have “a personal interest in health and nutrition and are passionate about preparing healthful food for the children they serve.” She says, “Being an RD who supports a CACFP preschool program can be very gratifying. Knowing that children are being served healthful foods in a childcare environment helps promote a healthier lifestyle that can be carried into adulthood.”

Legislative advocacy is another opportunity for RDs interested in CACFP. HR 5003, a bill that was recently approved by the House Education and Workforce Committee, may be voted on during the next Congressional session. A Senate bill, which also will likely be considered, aims to decrease the administrative burden on childcare providers and would allow them more money to spend on food. Child nutrition advocates also hope to make it simpler for childcare homes to receive Tier I funding, since studies show that providers receiving higher reimbursements spend significantly more on food than those with lower reimbursements ($2.36 vs $1.96 per child per day), according to Monsivais and colleagues.

Lipscomb points out that CACFP, because it targets the nation’s youngest children, is important as a preventive health strategy for a generation. By investing in nutrition early, as research on CACFP and its benefits have shown, knowledge about healthful choices and experience with healthful foods can help put children on the right dietary path for life.

— Christen Cupples Cooper, MS, RDN, is a doctoral candidate in nutrition education at Teachers College, Columbia University in New York City.