Food Labeling: Supporting Smarter Food Choices

Food Labeling: Supporting Smarter Food Choices

By Mindy Hermann, MBA, RDN

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 25 No. 9 P. 10

Standardized labels and definitions may help consumers make more healthful, sustainable decisions

Front-of-pack labeling aims to help consumers make more informed food choices. Several labeling systems have been introduced in the United States, including Facts Up Front and various supermarket ratings, but no single system has been adopted nationwide. This can create inconsistency and confusion among consumers’ shopping decisions. In contrast, Europe’s NutriScore1 is a five-color rating system that adds and subtracts points from positive and negative nutrients and then assigns a grade and color based on the total score. Mexico recently began requiring warning seals for products exceeding recommendations for calories, total sugars, saturated fat, trans fat, and sodium.2,3 Brazil uses the NOVA system to identify foods based on degree of processing.4

In light of what other countries are doing, will the recent FDA initiative to update the definition of “healthy” result in a new front-of-pack system in the United States, and will it improve Americans’ food choices?5 In addition, with the ever-increasing environmentally minded shopper, will new climate labeling efforts help consumers choose climate-friendly foods and beverages?

Aligning ‘Healthy’ With the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

In the fall of 2022, the FDA announced a proposed update of the “healthy” claim as part of its top nutrition initiatives to reduce chronic disease and advance health equity. The existing “healthy” claim, introduced nearly 30 years ago in 1994, focuses on nutrient content. It sets limits for negative nutrients—total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium— and requires that a food carrying a “healthy” claim also provide at least 10% DV for the positive nutrients, such as vitamins A and C, calcium, iron, protein, and fiber. The proposed update shifts guidance from individual nutrients to the food groups defined in the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).

Americans continue to fall short of DGA recommendations, which is a motivating factor behind the FDA’s updated claim. More than half of Americans don’t meet the daily recommendations for vegetables, fruits, and dairy though they exceed guidance around grains and protein foods. Most Americans also exceed the DGA limits for added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. Because people typically make choices based on foods and not nutrients, the FDA is focusing its claim on helping consumers make more healthful, nutrient-dense choices.

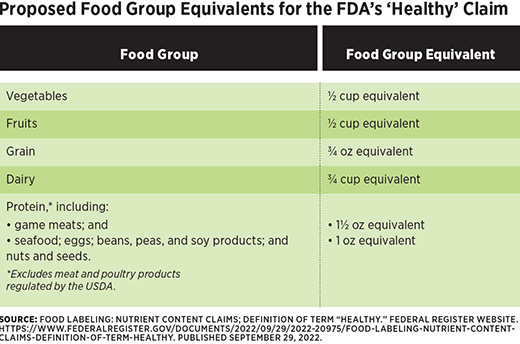

The updated definition of the claim “healthy” requires a food product to contain a predefined amount of at least one food group or subgroup based on Reference Amount Customarily Consumed (RACC). Certain foods, namely raw, whole fruits and vegetables, automatically qualify for the “healthy” claim. In addition, products with ingredient statements that imply healthfulness, such as “contains X servings of fruit” or “beans are high in fiber,” also must include a content claim, for example, “contains 6 g fiber per serving.” Foods with a “healthy” claim also must fall within set limits for added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. The proposed baseline limits for negative nutrients are no more than 5% DV for saturated fat and added sugars and no more than 10% DV for sodium per RACC.

As with other claims, the use of the term “healthy” is voluntary. And while the new claim definition hasn’t yet been finalized, food group equivalents have been proposed (See Chart below).

The FDA’s ‘Healthy’ Claim vs AHA’s Heart-Check Mark

Independent of the FDA, the American Heart Association (AHA) established the Heart-Check mark program in 1995 to give consumers an easy, reliable system for identifying heart-healthy foods as a first step in building a sensible eating plan.6 Shelley Johnson, the Denver-based senior program lead for food systems and Heart-Check at the AHA, says that “use of the Heart-Check mark on food labeling is considered an implied health claim, which is different from the nutrient content claims associated with the FDA definition of ‘healthy.’ For a food to use this coronary heart disease health claim, it must contain a certain limit of total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, and sodium and meet a minimum standard of beneficial nutrients such as protein, fiber, or specific vitamins or minerals. The AHA has added requirements to the Heart-Check program that restrict sodium and added sugars.” It’s possible for a food to carry both the Heart-Check mark and a “healthy” claim, but neither one guarantees meeting the requirements for the other.

Climate Labels Communicate Sustainability

Just as consumers may desire more healthful food products with labels designating them as such, they have a growing need for sustainable and climate-friendly options that boast labels stating their environmental impact. According to research by the Hartman Group, a Washington State–based company providing research, analysis, and consulting services to help food and beverage brands, consumers in the United States increasingly associate carbon emissions and reducing carbon footprint with sustainability.7 The company’s research has found that consumers react better to climate-positive terminology compared with labeling for carbon impact. The United States doesn’t yet have a standard climate impact label system or agreed-upon definitions for communicating climate impact, but a handful of individual companies and organizations have begun to place climate-related labels on their products. The dairy alternative company Oatly recently introduced climate footprint labeling on its oat-based yogurts sold in North America.8 The labels express climate footprint in terms of kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalents per kilo of packaged food product, calculated on a life-cycle assessment from grower to grocer. Calculations are validated by the Sweden-based climate change organization CarbonCloud.

According to Blue Sky Consulting Group’s project archives, Carbon Label California “brings academics, environmentalists, business leaders, and policymakers together to design a Greenhouse Gas Content Label for consumer products in California” and develop a life-cycle assessment–based approach for measuring the carbon content of most California products manufactured or sold.9 Several start-up companies with climate-related label programs in the United States have ceased operations, suggesting that climate labeling isn’t ready for broad adoption in this country.

Foodservice company Chartwells Higher Education recently added labels to menus and dining facility signage to highlight the environmental impact of menu offerings.10 The company works with HowGood, self-described as the industry’s largest product sustainability database that has impact data on more than 2 million products derived from over 600 independent data sources and certifications, including the FDA and USDA. According to HowGood’s website, companies can formulate products and receive a running tally of their products’ carbon footprint, reach carbon reduction goals by identifying ingredients driving risk, and plan recipe changes to reduce carbon and water footprints.11 Menu items receive an environmental and social rating of good, great, or best based on environmental impact compared with environmental impact of standardized recipes for those items, for example, Company X’s macaroni and cheese compared with a benchmark recipe. Hartman Group research results suggest that this type of positive approach might resonate with consumers.

A 2022 Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health study funded by Foundation Earth and published in JAMA Network Open explored the effect of climate impact labels on potential fast-food choices.12 More than 5,000 online participants were shown a sample fast-food menu. The menu shown to one group of participants included nonred meat menu items such as chicken sandwiches with a green-colored “low climate impact” label, along with red meat items without a label. Another group viewed a menu that tagged red meat burgers with a red “high climate impact” and didn’t label nonred meat items. The control group received a menu without positive or negative climate impact labels. Study participants were asked to choose a single item for dinner, and both the high and low climate impact labels reduced red meat selections compared with the control group, with the red high impact labels having the strongest effect.

Making Sense of Food Labels

While standardized labels and definitions haven’t been adopted nationwide, they could benefit American consumers. “For example, an FDA-compliant ‘healthy’ claim on a food product label can help consumers recognize products that meet the updated criteria,” says Lauren Swann, MS, RD, LDN, a food labeling specialist in Bensalem, Pennsylvania. “Keep in mind that the new definition should also be used together with the Nutrition Facts panel and ingredient list to provide a clear guide to a product’s healthfulness.” Swann also says that the majority of branded products that qualify for the current “healthy” claim may not end up using it because the term “healthy” may not be appealing to consumers and could have the opposite effect on food choices if consumers think that healthy foods don’t taste good.

— Mindy Hermann, MBA, RDN, is a food and nutrition communications consultant in metro New York.

References

1. Nutriscore. Sante Publique France website. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/en/nutri-score. Updated August 1, 2023.

2. Official Mexican standard NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, general labeling specifications for prepackaged foods and non-alcoholic beverages-Commercial and health information. Official Journal of Federation website. https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4010/seeco11_C/seeco11_C.htm

3. Ministry of economy published modifications to Mexican official standard NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, which sets forth the commercial and sanitary specifications matters of labeling for pre-packaged food and non-alcoholic beverages. Basham website. https://basham.com.mx/ministry-of-economy-publishes-modifications-to-mexican-official-standard-nom-051-scfi-ssa1-2010-which-sets-forth-the-commercial-and-sanitary-specifications-matters-of-labeling-for-pre-packaged-food-a/. Published March 31, 2020.

4. Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):604-612.

5. Food labeling: nutrient content claims; definition of term ‘healthy.’ Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/29/2022-20975/food-labeling-nutrient-content-claims-definition-of-term-healthy. Published September 29, 2022.

6. Heart-check certification. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/company-collaboration/heart-check-certification

7. Sustainability nomenclature gets nuanced. Hartman Group website. https://www.hartman-group.com/infographics/79201357/sustainability-nomenclature-gets-nuanced. Published August 28, 2023.

8. Product climate footprint explained. Oatly website. https://www.oatly.com/oatly-who/sustainability-plan/climate-footprint-product-label

9. Carbon Label California. Blue Sky Consulting Group website. https://www.blueskyconsultinggroup.com/project/15

10. Estrada R. How Chartwells Higher Ed's climate-labeling initiative is helping college campuses meet sustainability goals. Foodservice Director website. https://www.foodservicedirector.com/sustainability/how-chartwells-higher-eds-climate-labeling-initiative-helping-college-campuses. Published February 8, 2023.

11. Sustainability intelligence for food companies. HowGood website. https://howgood.com/

12. Wolfson JA, Musicus AA, Leung CW, Gearhardt AN, Falbe J. Effect of climate change impact menu labels on fast food ordering choices among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2248320.