November/December 2024 Issue

November/December 2024 Issue

The Rise of the Zero-Waste Grocery Store

By Jamie Santa Cruz

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 26 No. 9 P. 30

The challenge in the movement to make it mainstream.

Americans generate over 14 million tons of plastic packaging waste annually, with a significant portion coming from food packaging.1 This waste not only contributes to environmental pollution but also poses health risks due to plastics contaminating food.2,3

As awareness of these issues grows, a movement to cut packaging waste in grocery stores is gaining momentum. One notable development is the “zero-waste” grocery stores that have started popping up around the country. Although zero-waste stores are typically small specialty stores, large grocery chains and food manufacturing companies are also experimenting with ditching disposable packaging.

Here’s how the grocery industry is changing—and how dietitians can be part of the movement for a more sustainable future.

The Exploding Popularity of Local Zero-Waste Grocers

Zero-waste grocery stores are built on a simple idea: sell food package-free as far as possible.

Zero-waste stores typically have a warehouse or market-style setup that avoids individual packaging and allows customers to purchase from bulk bins. Instead of providing disposable packaging, these stores ask customers to bring their own reusable containers to fill.

Though the first zero-waste store didn’t open in the United States until 2012,4 the concept is now booming, with over 1,300 zero-waste stores currently operating across the country.5 From Precycle in Brooklyn, New York, to Nude Foods Market in Boulder, Colorado, to Byrd’s Filling Station in San Mateo, California, stores built on this model can now be found in many major metro areas and in some smaller cities as well.

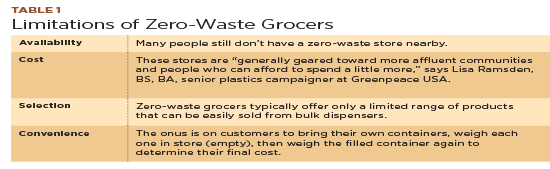

Despite their success, zero-waste stores have some limitations. These are shown below in Table 1.

Given these limitations, there’s a clear need for larger-scale solutions that are both more convenient and more economical, in order to tackle food packaging waste.

Large Retailers and Reusable Packaging

Large grocery chains have been slow to address packaging waste. A 2021 Greenpeace scored 20 of the top US retailers on their efforts in reducing the use of disposable plastic and gave all 20 failing scores.6

Several large retailers, including Sprouts, Whole Foods, Kroger, and Publix, have bulk sections in their stores, which could in theory support a culture of refilling. But as in boutique zero-waste stores, buying from bulk bins tends to be time-consuming, and supermarket bulk sections contain only a limited selection of products. Furthermore, although customers can in theory bring their own reusable containers, supermarkets almost always offer customers disposable plastic bags to use, meaning their bulk section often aren’t reducing packaging waste.7,8

That said, several companies are working to increase the convenience of the bulk aisle. SmartBins, a San Francisco Bay Area company, has developed sensor-driven bulk dispensers that automatically measure the amount of food dispensed, eliminating the need to weigh containers.9 Meanwhile, the Refill Coalition, a partnership among multiple grocery retailers in the United Kingdom, is working on standardized refill dispensers that similarly aim to automate the process and increase convenience.10

Increasingly, supermarkets are experimenting with a completely different model as well—namely, prefilled reusable packaging. Whereas the bulk-food model relies on consumers to bring in their own containers and fill themselves, the “prefill” model works differently: grocery stores or food manufacturers acquire reusable containers and prefill them with their products. Customers then grab and go.

This model is very convenient at the point of purchase, but the challenge is that customers need to return the container after use. Depending on the program, this happens in one of two ways:

1. Return on the go: Customers return the container to the store or another designated drop-off point.

2. Return from home: Containers are picked up by a collection service from the customer’s home.

Throughout much of the 20th century, US soda and beer companies ran on this model, selling their beverages in glass bottles on a deposit-return system (a “return on the go” scheme). Meanwhile, old-fashioned milk delivery services that drop off full bottles of milk on customers’ porches and pick up their empty bottles at the same time are an example of “return from home.”

Several US chains have recently experimented with prefilled reusable packaging. Starting in 2019, New Seasons Market, which operates 21 stores in the Pacific Northwest, implemented reusable packaging for certain products in its stores. To pull off the model, the grocery chain partnered with Bold Reuse, a company that handles the logistics of collecting customers’ empty containers and sanitizing them for reuse.11

Other large chains, including Walmart, Kroger, and Giant Food, have experimented with prefilled packaging as well. These retailers have all established trial programs with Loop, a company that, like Bold Reuse, distributes reusable packaging to brands, then collects the packaging after use and sanitizes it.12,13 Loop offers a limited range of products from brands like Proctor and Gamble, Nestle, and Mondelez in reusable packaging.14

But not all the forays into this new world have gone smoothly. Several retailers that established trial programs with Loop ended those trials without clear plans for expansion.15 New Seasons Market and Bold Reuse also ended their partnership earlier this year—though Bold Reuse CEO Jocelyn Quarrell explains the move as “more of a pivot than a quit. We are confident that refill and reuse is the future.”

These setbacks illustrate that a system of reuse has serious challenges. These include the following considerations.

Infrastructure

Setting up systems for collecting, sorting, sanitizing and refilling reusable packaging is complex.8 Companies like Bold Reuse and Loop are attempting to address this issue, but they have a “chicken and egg” problem, according to Crystal Dreisbach, MPH, CEO of Upstream, an agency advocating for the reuse movement in the United States and Canada. “You can’t grow your business to have the capacity to wash for a Whole Foods or [some other large company] unless you have the contracts to do it”—but it’s also impossible to get contracts without having the infrastructure to support them.

Cost

Reusable packaging can be cheaper long-term: the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a nonprofit that has extensively studied reuse/refill systems, estimates that companies could save $10 billion by replacing 20% of their single-use plastic packaging with reusable alternatives.16 But the initial investment in infrastructure to support reusable packaging is significant17—and customers are reluctant to pay the extra cost.8,18

Convenience and Customer Education

Research shows that consumers prefer recycling—which is now an established norm—to reuse,19 which is seen as inconvenient.8 Customers don’t always understand the value of reuse (compared with recycling) and so don’t choose reusable.20

Not Enough Reuse in Practice

Reusable packaging must be used a minimum number of times to be more environmentally friendly than single-use alternatives. But sometimes containers break, or customers don’t return them. In addition, reusable packaging naturally starts to show superficial wear over time, which can be a turnoff to customers and can potentially trigger companies to replace the packaging too quickly.18

Environmental Impact

In some reuse programs, the energy use, water use, and emissions involved in collecting, transporting, and sanitizing packaging mean that reusable packaging isn’t actually better for the environment.21 According to a 2020 report, 72% of studies that have looked at reusable packaging have found that it has environmental benefits over single-use packaging, but the rest were mixed or negative.22

System-Level Change: The Oregon Model

To achieve significant reductions in packaging waste, a systemic approach will be necessary. Single-use “is the norm for so many of us for so long. It’s a really ingrained part of our culture,” Dreisbach says. “In order to change the whole economy of how we package our food, you have a systems-level issue.”

What’s needed, then, is a system-level response, where all the actors in the United States’ entire grocery, food packaging, and food manufacturing industries move toward reuse. That means “reconsidering a lot of different parts of our food system and thoughtfully redesigning it from a linear model to one that allows for more circularity of packaging,” Quarrell says. “It’s not going to be an overnight effort.”

While it might take time, Oregon’s beverage industry offers an example of how systemic change can occur.

In 1971, Oregon passed the nation’s first “Bottle Bill,” a law that established a refund value for beverage bottles (to promote recycling). The law also required retailers to participate in the collection of the bottles.23

The new law prompted Oregon beverage distributors to band together to form the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative, which manages bottle collection through a statewide system of drop boxes. It also handles the flow of deposits and refunds for its members. The cooperative currently has a collection rate of 80% to 90%, compared with the national average beverage container recycling rate of about 35%.24

For years, the cooperative collected beverage bottles for recycling, not reuse. But because it already had bottle collection infrastructure in place, the cooperative was able to go a step further. In 2018, it launched the nation’s first statewide refillable bottle program.23

The program has proven to have both environmental and economic benefits. Each bottle gets reused about 25 times and has a 95% lower carbon footprint than nonrefillable bottles.25 And it also lowers packaging costs: the cost per use for a reusable bottle in the program is about half of the cost for a new, nonreusable bottle, according to Matt Swihart, cofounder of Double Mountain Brewery, which participates in the program.

Significantly, Double Mountain had already started using refillable bottles before the cooperative launched its larger-scale program. However, the brewery struggled to get traction as long as they were working alone trying to implement a system of reuse. “We had some marginal success [on our own], but we really did do a lot better once the cooperative came in,” Swihart says. “It made a lot of logistical headaches go away.” This experience illustrates the importance of industrywide cooperation and systemwide change over piecemeal efforts from individual companies.

Future Directions

For broader adoption of reuse systems, legislation of the kind that was passed in Oregon will be crucial. “For any scale, you definitely need a greater infrastructure and government policies that assist it or incentivize it,” Swihart says. “Assisting companies in setting up infrastructure, or having required targets for reuse, is going to be needed. It’s very, very important.”

Quarrell agrees on the importance of policy. Companies really need “support from cities and states to support this transition to reusable packaging. That is likely to include both sticks (bans or fees) and carrots, like tax incentives or public funding that can support the infrastructure.”

The United States is moving in this direction, albeit slowly. Ten US states now have bottle bills similar to Oregon’s,26 and a national bottle bill has been proposed as well.27,28 In addition to bottle bills, several states—Oregon, Colorado, California, and Maine—have recently passed a new kind of legislation for packaging called extended producer responsibility (EPR). EPR laws go beyond just beverages and require companies to take responsibility for other kinds of packaging waste as well.29 Although none of these laws technically mandate reuse, all of them help spur companies to collaborate on the kind of infrastructure that makes systems of reuse possible.

Tips for Reducing Packaging Waste

It’s impossible to completely avoid packaging waste, but Americans want to do so as much as possible. A 2022 survey found that 86% of consumers under age 45 said they would pay more for sustainable packaging, and 74% of consumers said they would be interested in buying products that come in refillable packaging.30

“People are feeling the need for reuse. There’s definitely demand for it,” Dreisbach says.

Meanwhile, dietitians are well-positioned to help guide clients on how to avoid food packaging waste. “Dietitians are among the most trusted voices on food information,” Chou says, citing a 2022 survey showing that dietitians had more public trust than any other information source on food.31 “It’s critical that we use our knowledge to support our communities with well-rounded evidence-based information to help people make informed decisions.”

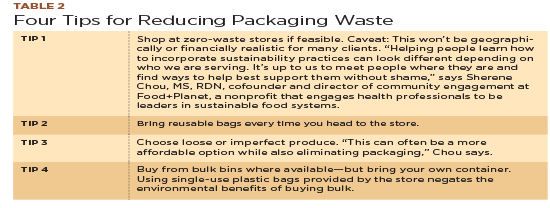

See Table 2 for a list of the top tips to reduce packaging waste dietitians can offer clients.

Finally, given that it’s currently very difficult to avoid packaging waste, dietitians can encourage clients to look beyond packaging. Tackling packaging waste is obviously a worthy effort, but other aspects of our food choices make an equally large or possibly larger difference for the environment—such as increasing vegetable intake and reducing meat consumption, which has a huge impact on an individual’s environmental footprint.32 In other words, even if a culture of reuse is still in the future, there are plenty of other environmentally friendly actions to take in the meantime.

— Jamie Santa Cruz is a freelance writer based in Parker, Colorado.

Plastic Substitutes

In the effort to avoid plastic, retailers and consumers alike often turn to glass or metal as a solution, or to plastics that are biodegradable or compostable. However, these forms of packaging are not automatically more environmentally friendly than single-use plastic.

Glass and metal are emissions-intensive to make, meaning that the environmental impact of producing a container out of these materials is greater than for a plastic container.33 Glass and metal can be more environmentally friendly than plastic, but only if they’re reused many times. Biodegradable plastics, meanwhile, don’t actually break down very easily. As for compostable plastics, there are few industrial composting facilities that can process these plastics, and those that exist often won’t accept compostable plastics because they can contaminate soil.34

Increasingly, therefore, experts on the topic are arguing that society needs to ditch the idea of single-use altogether, in favor of reuse.35

References

1. Plastics: material-specific data. US Environmental Protection Agency website. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data. Updated April 2, 2024. Accessed August 24, 2024.

2. Siddiqui SA, Bahmid NA, Salman SHM, et al. Migration of microplastics from plastic packaging into foods and its potential threats on human health. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2023;103:313-359.

3. Jadhav EB, Sankhla MS, Bhat RA, Bhagat DS. Microplastics from food packaging: an overview of human consumption, health threats, and alternative solutions. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2021;16:100608.

4. Pham D. First package-free, zero-waste grocery store in US opens in Austin, Texas. Inhabitat website. https://inhabitat.com/first-package-free-zero-waste-grocery-store-in-us-opens-in-austin-texas/. Published June 24, 2011. Accessed August 26, 2024.

5. The state of zero waste. Public Interest Research Group website. https://pirg.org/articles/the-state-of-zero-waste/. Published February 7, 2023. Accessed August 25, 2024.

6. Shopping for plastic: the 2021 supermarket plastics ranking. Greenpeace website. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/shopping-for-plastic-2021/. Published 2021. Accessed July 30, 2024.

7. Vann K. The problem with America’s bulk food bins. Eater website. https://www.eater.com/2019/10/29/20938213/bulk-food-grocery-store-supermarket-environmental-impact-plastic-packaging. Published October 29, 2019. Accessed August 25, 2024.

8. Coelho PM, Corona B, ten Klooster R, Worrell E. Sustainability of reusable packaging–current situation and trends. Resour Conserv Recycl: X. 2020;6:10037.

9. Vann K. Tech startups want to reinvent the bulk aisle—grocery’s most glorious, affordable, unwieldy section. That’s going to be harder than it looks. The Counter website. https://thecounter.org/modernizing-bulk-grocery-supermarkets-tech-shopping/. Published April 18, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2024.

10. The Refill Coalition website. https://www.refillcoalition.com. Accessed August 26, 2024.

11. Bold Reuse, New Seasons Market team on pilot to help food makers reuse glass packaging. New Seasons Market website. https://www.newseasonsmarket.com/getmedia/df6b58dc-e071-4c59-9cbf-d2c613806d11/NSM_Press-Release_Bold-Reuse-Pilot.pdf. Published April 14, 2023. Accessed August 25, 2024.

12. Anderson D. Walmart partners with Loop for reuse. Trellis website. https://trellis.net/article/walmart-partners-loop-reuse/. Published October 14, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2024.

13. Moran CD. Giant Food teams up with reusable packaging program Loop. Grocery Dive website. https://www.grocerydive.com/news/giant-food-teams-up-with-reusable-packaging-program-loop/628304/. Published July 28, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2024.

14. Rosengren C. TerraCycle promises ‘future of consumption’ with Loop reuse system. Waste Dive website. https://www.wastedive.com/news/terracycle-promises-future-of-consumption-with-loop-reuse-system/546596/. Published January 24, 2019. Accessed August 25, 2024.

15. Stevenson B. Trials and tribulations: how can retailers scale reuse and refill for good? Innovation Forum website. https://www.innovationforum.co.uk/articles/trials-and-tribulations-how-can-retailers-scale-reuse-and-refill-for-good. Published August 31, 2023. Accessed August 25, 2024.

16. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Reuse – rethinking packaging. https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/_A-BkCs_aXeX02_Am1z_J7vzLt/Reuse%20–%20rethinking%20packaging.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed August 25, 2024.

17. The UK Plastics Pact. Reusable packaging roundtables. https://www.wrap.ngo/sites/default/files/2023-09/UKPP%20Reuse%20Round%20Tables%20-%20Final%20Project%20Report%20Draft%20v9%20FINAL.pdf. Published August 2023. Accessed August 24, 2024.

18. Miao X, Magnier L, Mugge R. Switching to reuse? An exploration of consumers’ perceptions and behavior towards reusable packaging systems. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2023;193:106972.

19. Greenwood SC, Walker S, Baird H, et al. Many happy returns: combining insights from the environmental and behavioural sciences to understand what is required to make reusable packaging mainstream. Sustain Prod Consum. 2021;27:1688-1702.

20. Kunamaneni S, Jassi S, Hoang D. Promoting reuse behaviour: challenges and strategies for repeat purchase, low-involvement products. Sustain Prod Consum. 2019;20:253-272.

21. Plastic IQ Solutions Database. Plastic IQ website. https://plasticiq.org/solutions/reuse/. Accessed August 24, 2024.

22. Zero Waste Europe. Reusable vs. single-use packaging: a review of environmental impacts. https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/zwe_reloop_report_reusable-vs-single-use-packaging-a-review-of-environmental-impact_en.pdf.pdf_v2.pdf. Published February 12, 2020. Accessed August 28, 2024.

23. History of Oregon’s Bottle Bill. Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative website. https://obrc.com/oregons-bottle-bill/history-of-oregons-bottle-bill/. Accessed August 1, 2024.

24. How bottle bills compare. Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative website. https://obrc.com/results/how-bottle-bills-compare/. Accessed August 1, 2024.

25. Refill program. Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative website. https://obrc.com/partners/refill-program/. Accessed August 1, 2024.

26. State beverage container deposit laws. National Conference of State Legislatures website. https://www.ncsl.org/environment-and-natural-resources/state-beverage-container-deposit-laws. Updated March 13, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2024.

27. Washington Recycling and Packaging Act (SB 5154 / HB 1131): The WRAP Act. Zero Waste Washington website. https://zerowastewashington.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WRAP-Act-Handout-January-6-2023.pdf.Accessed August 25, 2024.

28. The break free from Plastic Pollution Act. Beyond Plastics website. https://www.beyondplastics.org/bffppa. Accessed August 25, 2024.

29. Extended producer responsibility. National Conference of State Legislatures website. https://www.ncsl.org/environment-and-natural-resources/extended-producer-responsibility. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed August 25, 2024.

30. 2022 global buying green report: preference for sustainable packaging remains strong in a changing world. Trivium Packaging website. https://www.triviumpackaging.com/news-media/reports/buying-green-report-2022/. Published April 22, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2024.

31. International Food Information Council. 2022 food and health survey. https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IFIC-2022-Food-and-Health-Survey-Report-May-2022.pdf. Published May 18, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2024.

32. Scarborough P, Clark M, Cobiac L, et al. Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. Nat Food. 2023;4:565-574.

33. Brock A, Williams ID. Life cycle assessment of beverage packaging. Detritus. 2020;13(13):47-61.