Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 21, No. 11, P. 42

Suggested CDR Learning Codes: 4130, 4180, 5190, 5310

Suggested CDR Performance Indicators: 8.3.1, 8.3.5, 8.3.7

CPE Level 3

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

Diabetes complicates an estimated 6% to 7% of pregnancies in the United States.1 The majority of cases present as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). GDM is diagnosed during pregnancy, and women with GDM had no previous indication of glucose intolerance before conception. In contrast to this are women with preexisting diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) who become pregnant. Preexisting diabetes poses more maternal and fetal risks than does gestational diabetes. In addition, unlike those with gestational diabetes, women with preexisting diabetes are aware of their diagnoses, so management should begin before conception.

As the rates of diabetes rise in the general public, so will the rates of preexisting diabetes during pregnancy. According to a large population-based study conducted in Ontario, Canada, between 1996 and 2010, the number of women with preexisting diabetes during pregnancy doubled.2

The risk of many complications associated with diabetes during pregnancy can be reduced through tight glycemic control. Therefore, it’s essential that health care providers, including RDs, be active participants in the support of these patients.

This continuing education course identifies the unique challenges, and examines the nutritional needs, of women with preexisting diabetes who become pregnant. Much of the focus on diabetes and pregnancy has been on women with gestational diabetes; however, women with preexisting diabetes present with different challenges and require a distinct approach. This course uses current evidence-based practice to provide diet, weight, and physical activity recommendations for RDs to support their role as active members of the health care team treating women with preexisting diabetes who become pregnant.

Maternal and Fetal Complications

During pregnancy, glucose is the primary source of energy for the growing fetus. Even in a pregnancy that’s not complicated by diabetes, glucose levels will fluctuate, as hormone levels influence insulin secretion and insulin resistance. The first trimester typically is a period of insulin sensitivity, while insulin resistance increases in the second and third trimesters, causing heightened insulin secretion to compensate. In women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, this process may be hindered, and complications can result.

The risk of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia rises during pregnancy. During the first trimester, women with type 1 diabetes are at high risk of hypoglycemia as insulin sensitivity increases and insulin needs decrease. Adjustments to insulin may be necessary, with many women seeing a decrease in their requirements during this time.1 As the pregnancy progresses to the second and third trimesters, hyperglycemia becomes a concern due to insulin resistance, and insulin requirements can increase by two or three times the prepregnancy needs.1 Women with type 1 diabetes likely will require frequent adjustments to their insulin regimens.3 For those with preexisting type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance may be greater throughout the course of pregnancy, and especially during the second and third trimesters, than for those with type 1 diabetes due to the higher prevalence of obesity in individuals with type 2 diabetes.1

Maternal complications of poor glycemic control during pregnancy include higher risk of the development of ketoacidosis, diabetic nephropathy, and hypertension.1,3 In addition, obesity in pregnancy, which commonly occurs with type 2 diabetes, is associated with higher risk of obstructive sleep apnea, preeclampsia, urinary tract infection, cesarean section delivery, difficult delivery, and perinatal mortality and morbidity.1

Potential fetal complications of preexisting diabetes in pregnancy include macrosomia, respiratory distress syndrome, hypocalcemia, polycythemia, hyperbilirubinemia, spontaneous abortion, neonatal hypoglycemia, and obesity and type 2 diabetes later in life.1 The presence of congenital anomalies (including cardiovascular, central nervous system, skeletal, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal) are more common in the babies of women with preexisting diabetes than in those without it, likely due to the presence of hyperglycemia during organogenesis in women with diabetes.1

Preconception Education

Given the high risk of complications in both mother and baby, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that all women with diabetes who are of reproductive age receive preconception screening and education. Organogenesis occurs during the first eight weeks of pregnancy. Given the known risks of hyperglycemia during this crucial time, if preconception education isn’t provided before the pregnancy, the negative effects of poor glycemic control early in pregnancy already may have occurred by the time of the first obstetric visit.

The ADA recommends that women with preexisting diabetes who are planning a pregnancy use appropriate contraception and be seen at one- to two-month intervals until glycemic control is stable, target A1c is achieved, and the risks of diabetes-related complications have decreased. At this time, contraception can be discontinued, but preconception care by a diabetes team should continue until pregnancy occurs. A free tool for health care practitioners, “Diabetes and Reproductive Health for Girls,” is available for download on the ADA website: www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/parents-and-kids/teens/reproductive-health-girls.html.4 In addition to blood glucose management strategies, preconception education also should include weight reduction counseling for women who are overweight or obese and discussion of the importance of folic acid supplementation.5,6

Monitoring

Given the risks of hyperglycemia during early pregnancy, the ADA recommends a hemoglobin A1c goal of 6.5% before conception to reduce the potential of congenital abnormalities.3,6,7 In early pregnancy, the A1c goal should be between 6% and 7%, allowing for individualization based on the maternal risk of hypoglycemia. During the later stages of pregnancy, the target A1c goal is 6% to 6.5%.6 Recent studies have shown that a hemoglobin A1c less than or equal to 5.9% may be an ideal level as the pregnancy progresses, especially for the prevention of macrosomia and preeclampsia, assuming this can be achieved without hypoglycemia.8,9 However, after conception, as maternal blood volume and red blood cell turnover increases, A1c levels naturally fall, and therefore the A1c is less reliable and should be used as a secondary measure of glycemic control with self-monitoring of blood glucose as the primary tool.3,6,10

Fasting and postprandial self-monitoring of blood glucose is recommended during pregnancy as the primary tool for evaluating glycemic control. The ADA recommends the following blood glucose targets for women with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes:

• Fasting: less than or equal to 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L); and either

– One-hour postprandial: less than or equal to 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L); or

– Two-hour postprandial: less than or equal to 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L).

Women with preexisting diabetes who are using insulin pumps or basal-bolus insulin regimens also should use preprandial testing.3 These target levels may be difficult for women with type 1 diabetes to achieve without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia; therefore, individualized care should provide less stringent targets to help them avoid hypoglycemia.3

Recent studies have, with conflicting results, examined the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in women with preexisting diabetes to achieve improved glycemic control. A large multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled study conducted in Europe and North America known as the CONCEPTT trial showed that the use of CGM in women with type 1 diabetes resulted in improved neonatal outcomes, including lower incidence of large for gestational age babies, fewer neonatal intensive care admissions lasting more than 24 hours, fewer incidences of neonatal hypoglycemia, and shorter length of hospital stay.11 However, other trials haven’t shown the same benefits. The GlucoMOMs trial, a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial conducted in the Netherlands observed that the use of CGM in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes resulted in no differences in maternal or fetal outcomes, including the incidence of macrosomia.10,12 Therefore, more research is necessary to determine whether CGM should be offered to women with preexisting diabetes during pregnancy.

Because pregnancy is a naturally ketogenic state, women with preexisting diabetes are at risk of the development of diabetic ketoacidosis at lower blood glucose levels than they were in the nonpregnant state. Women should be taught how to test their urine for ketones and should keep ketone strips at home.3,6

Medication Use

Insulin is the preferred medication for the management of blood glucose in pregnant women with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, as it hasn’t been found to cross the placenta.3,6 In women with type 2 diabetes who were on oral antihyperglycemic medications before pregnancy, these medications typically are discontinued and insulin is initiated as needed, preferably before conception. However, in some cases, it may be determined that women who haven’t been fully transitioned to insulin should remain on their previously prescribed oral antihyperglycemic medications during the early weeks of the pregnancy to ensure tight glycemic control during organogenesis.13 Insulin needs likely will fluctuate throughout the pregnancy, with decreased need during the early weeks and a rapid increase starting in the second trimester. Some women may have a leveling off or even require a small decrease in their insulin needs late in the third trimester. Changes to the insulin regimen may need to be made on a weekly or biweekly basis.3

Oral agents typically aren’t initiated during pregnancy; however, there’s some debate as to whether antihyperglycemic medications should be used in women with preexisting type 2 diabetes who aren’t compliant with insulin or refuse to take it. The National Institute for Heath and Clinical Excellence Guideline states that metformin, the first-line treatment used in nonpregnant patients with diabetes, may be used by pregnant women with preexisting diabetes as an adjunct or alternative to insulin.14 A recent retrospective analysis of 540 women with gestational diabetes during pregnancy found no significant adverse maternal or fetal outcomes with metformin use initiated in the first trimester compared with metformin use initiated after the first trimester or insulin use alone. These outcomes included premature birth, respiratory distress, birth trauma, five-minute Apgar score, neonatal hypoglycemia, the need for phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal anthropometric measurements, maternal glycemic control, maternal hypertensive complications, and postpartum glucose tolerance. However, there was a significant increase in premature birth rates among all patients treated with metformin during the first and/or second trimesters compared with those treated with only insulin, which has been demonstrated in other trials comparing the use of insulin vs metformin.15

Recent studies also have examined the safety and efficacy of glyburide, another commonly prescribed oral antihyperglycemic agent, in pregnant women with diabetes. A recent prospective, randomized controlled study comparing the use of metformin vs glyburide in women with GDM showed similar safety and efficacy of the two medications.16 A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials published in 2017 comparing the use of glyburide vs insulin in patients with GDM showed no significant difference in maternal glycemic control and other maternal outcomes (including weight gain, need for cesarean section, and gestational age at delivery). In addition, no significant difference was observed in fetal birth weight, including macrosomia. However, it’s important to note there was a higher incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in patients treated with glyburide.17

Most of the research on the use of antihyperglycemic medications has been conducted in patients with GDM as opposed to preexisting diabetes. Of note, a large interventional trial, the Metformin in Women With Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy Trial, is underway to investigate whether the addition of metformin will help with blood sugar control, lower insulin needs, and improve fetal outcomes in pregnant women with preexisting type 2 diabetes.18

Weight Gain During Pregnancy

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy can result in complications for both mother and baby. Being overweight or obese during pregnancy increases the risk of congenital abnormalities, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, preterm labor, cesarean section, greater maternal weight retention following delivery, maternal death, fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death.5,19,20 Therefore, one of the key recommendations for all health professionals is to identify early those women who are at higher risk of excessive weight gain during pregnancy to help guide appropriate weight gain targets.1

The standard of practice for gestational weight gain was most recently established by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and its use is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.21,22 Although the IOM doesn’t specifically address weight gain in women with preexisting diabetes, the same targets are used for pregnant women with preexisting diabetes as those used for women without diabetes.1 The recommended ranges of total weight gain based on prepregnancy BMI are outlined below and can be found at www.nap.edu/read/18291/chapter/1.21 Counseling for appropriate weight gain during pregnancy in women with diabetes should include discussion of a healthful dietary pattern at a sufficient calorie intake to avoid excessive weight gain, as well as the importance of physical activity.

Weight Gain Targets During Pregnancy

• Prepregnancy BMI <18.5 = 28 to 40 lbs (1 lb/week during the second and third trimesters);

• Prepregnancy BMI 18.5 to 24.9 = 25 to 35 lbs (1 lb/week during the second and third trimesters);

• Prepregnancy BMI 25 to 29.9 = 15 to 25 lbs (0.6 lb/week during the second and third trimesters); and

• Prepregnancy BMI ≥30 = 11 to 20 lbs (0.5 lb/week during the second and third trimesters).

MNT in Pregnancy

The goals of MNT for pregnant women with diabetes are to provide adequate calorie intake for appropriate weight gain while avoiding excessive weight gain, prevent maternal ketoacidosis, keep blood glucose levels within target ranges, and provide adequate nutrients to support both maternal and fetal health.1 In addition, as it should in nonpregnant women with diabetes, MNT should include strategies to help lower blood pressure and lipid profiles to reduce the risk of CVD and stroke.23

As with nonpregnant individuals with diabetes, it’s recommended that all pregnant women with diabetes seek counseling with an RD or other qualified diabetes educator for customized nutrition recommendations based on several factors, including type of preexisting diabetes, medication/insulin use, prepregnancy weight, comorbid health conditions, and personal preferences.

Dietary Patterns

According to both the ADA and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (the Academy), evidence suggests there’s no one dietary pattern that’s ideal for patients with diabetes and that nutrition prescriptions should be individualized.23-25 The ADA states, “Macronutrient distribution should be based on individualized assessment of current eating patterns, preferences, and metabolic goals.”26 This is supported by a systematic review that included 98 studies conducted between 2001 and 2010 to examine the effects of macronutrients, food groups, and eating patterns on the management of diabetes. The authors concluded that there are multiple eating patterns that can effectively contribute to improved glycemic control and reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes.27 Patients’ eating preferences, which may be based on religion, culture, health beliefs, economic status, and/or food availability, also must be taken into account.

Certain dietary patterns that have been shown in the research to have positive effects in the management of diabetes include the Mediterranean diet, DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, plant-based diets such as vegetarian and vegan diets, low-fat diets, and lower-carbohydrate diets.23,28-31

Energy

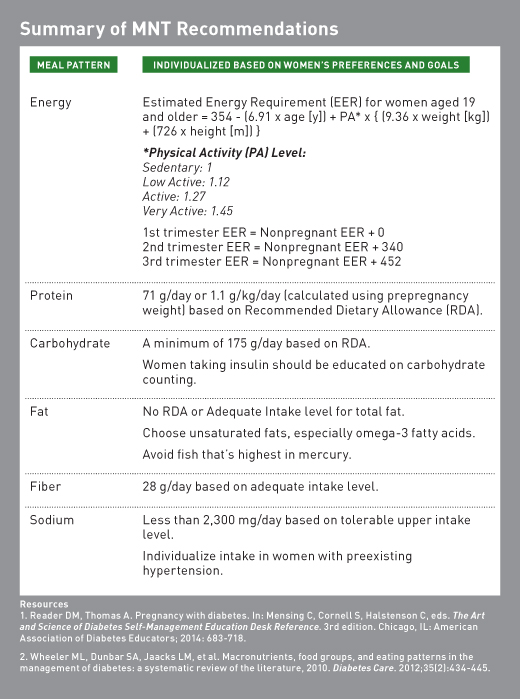

During pregnancy, estimated calorie requirements can be determined by using the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI).1 The DRI’s Estimated Energy Requirements (EER) are based on age, height, weight, and physical activity level. There are specific calculations used for pregnancy that change according to each trimester.32 See the table above for EER formulas. In women with preexisting diabetes, energy levels may need to be adjusted to provide for fetal growth and avoid ketonemia. All women with preexisting diabetes, and especially those with type 1 diabetes, should have ketone strips at home and receive education on testing for the presence of ketones.1,3

Protein

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein during pregnancy increases to 71 g/day, or 1.1 g/kg/day (based on prepregnancy weight).32 For women with concurrent kidney disease, dietary protein shouldn’t be restricted.23,26,33

Carbohydrate

There’s no evidence to suggest an ideal carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes.23,26 However, it’s essential that a pregnant woman not overly limit her intake of carbohydrate to an amount less than the RDA for pregnancy of 175 g per day, which is determined as adequate to support fetal growth.1,27 The amount and distribution of carbohydrate should be individualized based on type of diabetes, insulin use, food preferences, blood glucose levels, and physical activity level.1,25 Carbohydrate food choices should be primarily in the form of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and dairy products. Sources of carbohydrates that contain added fats, sugars, and sodium should be limited, and sugar-sweetened beverages should be avoided.26

For women taking insulin, a primary focus of MNT should be teaching them how to adjust insulin doses based on planned carbohydrate intake or how to eat with a consistent carbohydrate intake pattern for those on fixed daily insulin doses.23,25 Learning to “match” mealtime insulin to carbohydrate amount consumed to keep blood glucose levels at target should be a goal of MNT. Carbohydrate counting can be used as an effective tool for the management of glycemic control. A 2014 systematic review demonstrated a positive trend in the reduction of hemoglobin A1c in patients with type 1 diabetes using insulin.34 It’s important to note that insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios will change over the course of the pregnancy, and, therefore, regular blood glucose monitoring is vital.1

Fat

There’s no ideal fat intake for individuals with diabetes, and fat quality appears to be more important than quantity.26 Individuals with diabetes are encouraged to choose fat sources higher in unsaturated fatty acids. Specifically, an increase in intake of foods containing the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, as well as alpha-linolenic acid, is recommended because of the beneficial effects on cardiovascular health outcomes.23 As with the general public, individuals with diabetes should be encouraged to consume at least two servings per week of fish (particularly fatty fish).23 Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation doesn’t appear to have a beneficial effect on glycemic control.27

The recommendation to consume at least two servings of fish per week is appropriate for women with preexisting diabetes who are pregnant given the known benefits of omega-3 fatty acids on fetal development. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, is associated with improved infant visual and cognitive development.24 However, education should be provided on appropriate fish choices to help women avoid excessive mercury intake. Examples of lower-mercury fish include cod, flounder, haddock, salmon, sole, tilapia, and trout. Fish highest in mercury levels, which should be avoided during pregnancy, are king mackerel, marlin, orange roughy, shark, swordfish, tilefish, and bigeye tuna. Canned albacore tuna fish may be eaten in moderation (no more than one serving per week); however, canned light tuna may be eaten more frequently (two to three servings per week).35

Dietary Fiber

Intake of dietary fiber should follow guidelines for the general public. During pregnancy, the Adequate Intake for dietary fiber is 28 g/day.32 While there’s sparse evidence to support the beneficial effects of moderate fiber intake on glycemic control specifically, research has widely supported that dietary fiber intake is associated with lower all-cause mortality and a positive effect on cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with diabetes.23 A prospective cohort study published in 2012 that examined the association of dietary fiber intake with mortality risk in 6,192 patients with diabetes living in Europe concluded that higher-fiber intake was associated with decreased mortality risk.36 Other studies specifically examining the effects of the intake of high-fiber foods such as vegetables, legumes, fruits, whole grains, and bran also have concluded the beneficial impact of fiber intake on reduction of both CVD-specific mortality and all-cause mortality among patients with diabetes.37,38 Of note, one recent study, the TOSCA.IT study, found that fiber intake greater than 15 g/1,000 kcal (30 g/day on a 2,000-kcal diet) consumed resulted in lower hemoglobin A1c than did a lower dietary fiber intake.39

According to the Academy’s Evidence Analysis Library, “The registered dietitian nutritionist should encourage adults with diabetes to consume dietary fiber from foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.”24,25 In addition, as pregnant women tend to suffer from constipation, adequate fiber intake may help provide some relief for these symptoms.

Nonnutritive Sweeteners

Seven nonnutritive sweeteners are approved for use by the FDA (saccharin, acesulfame potassium, sucralose, neotame, advantame, steviol glycosides, and luo han guo fruit extract).40 Nonnutritive sweeteners may assist with weight loss through their potential to reduce daily calorie and carbohydrate intake as long as additional calories aren’t consumed in compensation.23 However, intake of nonnutritive sweeteners hasn’t been shown to have a significant independent impact on A1c, fasting glucose levels, or insulin levels.24,25 A randomized controlled trial published in 2017 investigated the effects of sucralose on glycemic control in patients without diabetes. The authors concluded that sucralose had no effect on blood glucose.41

There’s limited research on the safety of these sugar substitutes during pregnancy, and pregnant women with diabetes should discuss this with their obstetricians before using the substitutes.5 However, according to the American Pregnancy Association, saccharin should be avoided in pregnancy due to its potential to cross the placenta and remain in fetal tissue.42

Sodium

The ADA recommends that individuals with diabetes who don’t have hypertension follow the recommended sodium intake for the general population, which is less than 2,300 mg/day. Individuals with both diabetes and hypertension should receive individualized recommendations for further decreasing sodium intake.23 The DRI tolerable upper intake level for sodium intake for pregnant women is the same as the ADA recommendation for diabetes, 2,300 mg/day. Women with preexisting diabetes who are pregnant should follow these guidelines. Those with preexisting chronic hypertension are more likely to experience preeclampsia than are women without preexisting hypertension; however, there’s no evidence that salt restriction reduces the risk of developing preeclampsia.5,43

As per the table listed earlier, based on tolerable upper intake levels, MNT recommendations for sodium suggest less than 2,300 mg/day, and intake should be individualized in women with preexisting hypertension.1,27

Physical Activity

The benefits of physical activity have long been established. Physical activity is a cornerstone of diabetes treatment, known to improve blood glucose control and help maintain appropriate body weight. There’s strong evidence to support the routine practice of moderate-intensity physical activity during pregnancy.44 Physical activity during pregnancy has been shown to support cardiovascular fitness, help control maternal weight gain, and reduce the risk of postpartum depression.45-47 In a low-risk pregnancy, moderate-intensity physical activity hasn’t been shown to increase risk of low birth weight, preterm delivery, or miscarriage, and has been shown to result in decreased risk of hyperglycemia, development of gestational diabetes, lower overall gestational weight gain, and weight retention.5,44,48 Physical activity guidelines have been established for women during pregnancy and the postpartum period and should be adopted by women with preexisting diabetes based on activity level before pregnancy, assuming there are no medical contraindications.

The key physical activity guidelines for women during pregnancy and the postpartum period are as follows44:

• “Healthy women who are not already highly active or doing vigorous-intensity activity should get at least 150 minutes (two hours and 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Preferably, this activity should be spread throughout the week.”

• “Pregnant women who habitually engage in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity or are highly active can continue physical activity during pregnancy and the postpartum period, provided that they remain healthy and discuss with their health care provider how and when activity should be adjusted over time.”

Essentially, women who are physically active before pregnancy may, with the consent of their health care team, maintain a similar level of physical activity during pregnancy as they did before pregnancy, and women who were not physically active before pregnancy should aim to increase their level of activity to a goal of 150 minutes per week.

Discussion with a health care provider is recommended to determine need to adjust activity type or level over time.

It’s important that women with diabetes be educated on the need to monitor blood glucose levels before, during, and after physical activity. Before physical activity, women should consume a carbohydrate-rich snack if measured blood glucose levels are <100 mg/dL and they’re taking insulin.1 All women should carry a source of readily available glucose, such as glucose tabs, at all times while engaging in physical activity in case of hypoglycemia.

Managing Morning Sickness

“Morning sickness,” or nausea and vomiting during pregnancy (which can occur at any point throughout the day) is a common occurrence among pregnant women both with and without preexisting diabetes. Morning sickness generally begins around the sixth week of pregnancy and ends at about the start of the second trimester. For some women, the degree of nausea and vomiting can be more severe than for others. Inability to eat regular meals or frequent vomiting can pose challenges for the management of blood glucose levels in women with diabetes.

Management of blood glucose during morning sickness is similar to “sick day” strategies for nonpregnant individuals with diabetes. Often, small regular meals will help alleviate the symptoms of morning sickness. In the case of severe nausea or vomiting, efforts should be made to consume at least 8 oz of fluid every hour, with one of these being a sodium-rich fluid such as bouillon every third hour. Carbohydrate intake should be 150 to 200 g over the course of the day, often best tolerated in divided doses. Soft or liquid foods such as applesauce, yogurt, and ice cream can be used as a source of carbohydrate if better tolerated. Blood glucose levels should be tested every two to four hours until symptoms subside, and urine should be tested for ketones.1

Final Thoughts

Women with preexisting diabetes face challenges throughout the course of their pregnancies. The risks of complications for both mother and baby are higher in women with preexisting diabetes than in those without diabetes or in those who develop gestational diabetes during their pregnancy. Blood glucose management, diet choices, and appropriate weight gain are crucial to reducing the risks of complications and supporting the development of a healthy baby. By understanding the principles of nutrition management, along with the ability to individualize care based on the mother’s unique needs, RDs, as part of the health care team, are well positioned to help support these women.

— Diana Fischmann Orenstein, MS, MSEd, RD, LDN, CNSC, is a Boston-based dietitian whose private practice, Fresh Start Women’s Nutrition (www.fswomensnutrition.com), specializes in nutritional counseling for women’s health through the lifespan.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals should be better able to:

1. Explain how physiological changes that occur as a result of pregnancy can affect blood glucose management in women with preexisting diabetes.

2. Select and interpret the correct methods of blood glucose monitoring during pregnancy.

3. State the principles of MNT for pregnant women with preexisting diabetes.

4. Calculate the correct nutrient needs for women with preexisting diabetes, including calories, protein, and carbohydrate.

5. Demonstrate an understanding of current recommendations for weight gain and physical activity during pregnancy.

CPE Monthly Examination

1. During the first trimester, the risk of hypoglycemia increases in pregnant women with preexisting diabetes, especially type 1 diabetes, because of what physiological effect of pregnancy?

a. Insulin sensitivity increases during the first trimester.

b. Insulin resistance increases during the first trimester.

c. Insulin needs increase during the first trimester.

d. Appetite increases during the first trimester.

2. The American Diabetes Association recommends that, before conception, hemoglobin A1c be at what target level?

a. 6.5%

b. 7%

c. 7.5%

d. 8%

3. Following conception, hemoglobin A1c should be used as a secondary measure of glycemic control for which of the following reasons?

a. After conception, maternal blood volume and red blood cell turnover decreases and A1c levels naturally remain stable.

b. After conception, maternal blood volume and red blood cell turnover increases and A1c levels naturally fall.

c. After conception, maternal blood volume and red blood cell turnover decreases and A1c levels naturally rise.

d. There are no established reference values for hemoglobin A1c in pregnancy.

4. What is the target fasting blood glucose level in a pregnant woman with diabetes?

a. Less than or equal to 85 mg/dL

b. Less than or equal to 95 mg/dL

c. Less than or equal to 100 mg/dL

d. Less than or equal to 105 mg/dL

5. Based on the Institute of Medicine’s standard of practice for gestational weight gain, a woman with preexisting diabetes whose prepregnancy BMI was 27.3 should gain how much total weight over the course of her pregnancy?

a. 11 to 20 lbs

b. 15 to 25 lbs

c. 25 to 35 lbs

d. 28 to 40 lbs

6. Which of the following meal patterns does evidence show to be effective in the management of diabetes?

a. A very high-carbohydrate diet

b. A minimal-protein diet

c. The DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet

d. A high-fat diet

7. What is the Recommended Dietary Allowance for carbohydrate in pregnancy?

a. 160 g/day

b. 175 g/day

c. 200 g/day

d. 225 g/day

8. According to this course, which of the following fish should be avoided during pregnancy?

a. Flounder

b. Swordfish

c. Canned albacore tuna

d. Canned light tuna

9. While there’s a lack of evidence to support the beneficial effects of moderate fiber intake on glycemic control specifically, pregnant women with diabetes should be encouraged to consume dietary fiber from foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes for what potential benefit?

a. Increased fiber intake may provide some relief from constipation.

b. Increased fiber may provide some relief from heartburn symptoms.

c. Additional calcium intake is desirable during pregnancy.

d. Additional zinc intake is desirable during pregnancy.

10. According to the American Pregnancy Association, which of the following nonnutritive sweeteners should be avoided in pregnancy due to its potential to cross the placenta and remain in fetal tissue?

a. Sucralose

b. Saccharin

c. Neotame

d. Acesulfame potassium

References

1. Reader DM, Thomas A. Pregnancy with diabetes. In: Mensing C, Cornell S, Halstenson C, eds. The Art and Science of Diabetes Self-Management Education Desk Reference. 3rd edition. Chicago, IL: American Association of Diabetes Educators; 2014:683-718.

2. Feig DS, Hwee J, Shah BR, Booth GL, Bierman AS, Lipscombe LL. Trends in incidence of diabetes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: a large, population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 1996-2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1590-1596.

3. American Diabetes Association. Management of diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S114-S119.

4. Diabetes and reproductive health for girls. American Diabetes Association website. http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/parents-and-kids/teens/reproductive-health-girls.html. Accessed November 10, 2018.

5. Procter SB, Campbell CG. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(7):1099-1103.

6. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

7. American Diabetes Association. 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S137-S143.

8. Mañé L, Flores-Le Roux JA, Beniages D, et al. Role of first-trimester HbA1c as a predictor of adverse obstetric outcomes in a multiethnic cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(2):390-397.

9. Hughes RC, Moore MP, Gullam JE, Mohamed K, Rowan J. An early pregnancy HbA1c ≥5.9% (41 mmol/mol) is optimal for detecting diabetes and identifies women at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):2953-2959.

10. Yamamoto JM, Murphy HR. Emerging technologies for the management of type 1 diabetes in pregnancy. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(1):4.

11. Feig DS, Donovan LE, Corcoy R, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes (CONCEPTT): a multicentre international randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2347-2359.

12. Voormolen DN, DeVries JH, Kok M, et al. 488: Efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring in diabetic pregnancy, the glucomoms trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(Suppl 1):S288.

13. Greene MF, Bentley-Lewis R. Pregestational diabetes mellitus: glycemic control during pregnancy. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pregestational-diabetes-mellitus-glycemic-control-during-pregnancy. Updated September 10, 2018.

14. Guideline Development Group. Management of diabetes from preconception to the postnatal period: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;336(7646):714-717.

15. Vanlalhruaii, Dasgupta R, Ramachandran R, et al. How safe is metformin when initiated in early pregnancy? A retrospective 5-year study of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus from India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:47-55.

16. Nachum Z, Zafran N, Salim R, et al. Glyburide versus metformin and their combination for the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):332-337.

17. Song R, Chen L, Chen Y, et al. Comparison of glyburide and insulin in the

management of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182488.

18. Feig DS, Murphy K, Asztalos E, et al. Metformin in women with type 2 diabetes in pregnancy trial (MiTy): a multi-center randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):173.

19. Aune D. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1536-1546.

20. Baugh N, Harris DE, Aboueissa AM, Sarton C, Lichter E. The impact of maternal obesity and excessive gestational weight gain on maternal and infant outcomes in Maine: analysis of pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system results from 2000 to 2010. J Pregnancy. 2016;2016:5871313.

21. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. Guidelines on weight gain & pregnancy. https://www.nap.edu/read/18291/chapter/1. Published 2013. Accessed November 9, 2018.

22. Committee opinion: weight gain during pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/Resources_And_Publications/Committee_Opinions/Committee_on_Obstetric_Practice/Weight_Gain_During_Pregnancy. Published January 2013. Accessed October 27, 2018.

23. Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S120-S143.

24. Diabetes (DM) guideline (2015). Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Evidence Analysis Library website. https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5305&cat=5595. Published 2016. Accessed November 10, 2018.

25. MacLeod J, Franz M, Handu D, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics nutrition practice guideline for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults: nutrition intervention evidence reviews and recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):1637-1658.

26. American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S38-S50.

27. Wheeler ML, Dunbar SA, Jaacks LM, et al. Macronutrients, food groups, and eating patterns in the management of diabetes: a systematic review of the literature, 2010. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):434-445.

28. Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Ciotola M, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on the need for antihyperglycemic drug therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(5):306-314.

29. Boucher JL. Mediterranean eating pattern. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(2):72-76.

30. Cespedes EM, Hu FB, Tinker L, et al. Multiple healthful dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes in the women’s health initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(7):622-633.

31. Campbell AP. DASH eating plan: an eating pattern for diabetes management. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(2):76-81.

32. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dietary Reference Intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. https://www.nap.edu/read/11537/chapter/1. Published 2006.

33. KDOQI. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(2 Suppl 2):S12-S154.

34. Schmidt S, Schelde B, Nørgaard K. Effects of advanced carbohydrate counting in patients with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2014;31(8):886-896.

35. Eating fish: what pregnant women and parents should know. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm393070.htm. Updated November 29, 2017.

36. Burger KN, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, et al. Dietary fiber, carbohydrate quality and quantity, and mortality risk of individuals with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43127.

37. He M, van Dam RM, Rimm E, Hu FB, Qi L. Whole-grain, cereal fiber, bran, and germ intake and the risks of all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality among women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2010;121(20):2162-2168.

38. Nöthlings U, Schulze MB, Weikert C, et al. Intake of vegetables, legumes, and fruit, and risk for all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in a European diabetic population. J Nutr. 2008;138(4):775-781.

39. Vitale M, Masulli M, Rivellese AA, et al. Influence of dietary fat and carbohydrates proportions on plasma lipids, glucose control and low-grade inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes — The TOSCA.IT Study. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(4):1645-1651.

40. Additional information about high-intensity sweeteners permitted for use in food in the United States. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/food/ingredientspackaginglabeling/foodadditivesingredients/ucm397725.htm. Updated February 8, 2018.

41. Grotz VL, Pi-Sunyer X, Porte D Jr, Roberts A, Richard Trout J. A 12-week randomized clinical trial investigating the potential for sucralose to affect glucose homeostasis. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;88:22-33.

42. Artificial sweeteners and pregnancy. American Pregnancy Association website. http://americanpregnancy.org/pregnancy-health/artificial-sweeteners-and-pregnancy/. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 27, 2018.

43. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

44. Chapter 7: additional considerations for some adults. Health.gov website. https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter7.aspx. Updated November 8, 2018.

45. Matsuzaki M, Kusaka M, Sugimoto T, et al. The effects of a yoga exercise and nutritional guidance program on pregnancy outcomes among healthy pregnant Japanese women: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(6):603-610.

46. Hui AL, Back L, Ludwig S, et al. Effects of lifestyle intervention on dietary intake, physical activity level, and gestational weight gain in pregnant women with different pre-pregnancy body mass index in a randomized control trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:331.

47. Aguilar-Cordero MJ, Sánchez-García JC, Rodriguez-Blanque R, Sánchez-López AM, Mur-Villar N. Moderate physical activity in an aquatic environment during pregnancy (SWEP Study) and its influence in preventing postpartum. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2019;25(2):112-121.

48. Wang C, Wei Y, Zhang X, et al. A randomized clinical trial of exercise during pregnancy to prevent gestational diabetes mellitus and improve pregnancy outcome in overweight and obese pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(4):340-351.